Good morning, Mr. Hulk.

Your breakfast is here. On the tray. Keep the drapes closed?

Of course.

Well, there’s some good news. And some bad news.

If you’re sure.

Bad news first, then.

On October 31, 2020, The Guardian drops what can be read as a variation on the Jamesian parable of American innocence and European experience. Same story, this time in reverse. The naivete of its author, Candice Pires, a citizen of the United Kingdom, is by turns heartbreaking and infuriating, stultifying and shocking, crazy-making and telling. One reaches the end of her tragicomedy with the urge to go looking for a stray, live grenade to throw oneself upon and so stop the brain busting madness induced by this accidentally released, passing flurry of sad-emoji/emoji-happy/flaky-emoji/emoji-profound contradictions. As is the case with most tales of a guileless American odyssey gone awry.

The most troubling contradiction in the series, though, likely reveals itself only after one turns away from the page, turns away from the screen, and looks around. A self-portrait that is revealing for all the wrong reasons, Pires’ take on America ironically demonstrates that she, through her confessions of amazement and disappointment, shares something with and, perhaps, knows something about the self-dealing country that the country does not fully know about itself.

The merry-go-round begins in 2015. It is the final year of the Obama administration. Ms. Pires, who describes herself as a brown person, decides to move with her husband from the UK to Portland, Oregon. With their three year old daughter in tow, they do so in the belief that they will arrive in the ultimate, liberal utopia–one apparently more ultimately liberal and utopian than any of those more handily found within the confines of the buzzkill European Union. She is aware, she writes, of a certain TV series that is set in her future home and that trafficks in all sorts of local, urban hippie and hipster cliches. Rather than mistrust these satiric, canned-laughter notions, the cliches are, evidently, exactly what she and her husband are eager to experience.

The family arrives. All is well. All is exactly as expected. Portland, she notes, is indeed a “laid-back place, full of quirky, outdoorsy people (the Patagonia sort, not hunting).” Marijuana is legal. The author and her family frequent “the popular, 24-hour Voodoo Doughnut store” and try wacky flavors “with names like Dirt and Pothole.” She notes, approvingly, that one can easily spot “adverts for yoga with goats and yoga with weed.” “Our plan,” she writes, “was to get a campervan and drive up and down the west coast under limitless blue skies.”

“Limitless blue skies”?

On the Oregon Coast? Where the sea and the sand and the rain and the clouds often mash up to resemble a sheet of static faintly wiggling on an expiring black and white television set?

It is becoming clear that the research department may not have performed its function with sufficient seriousness.

Time passes. Not by much, calendar-wise. Centuries, though, in the heart and head. Trump wins in 2016 and Pires, far from alone, is well gobsmacked, even though Britain had already smacked itself with the same wave of bleaching stupid. She also shortly learns that, thanks to the nonpartisan effects of global warming, the beckoning outdoors surrounding the new city sometimes catches on fire, which makes it hard to breathe. Portland, she discovers–somehow to her surprise–is not ethnically diverse. At all. To the contrary: 72.2% of the population, she reports, is white. Her biracial daughter is teased at school because of her skin color. Pires is ashamed of herself for placing her daughter in this potentially soul destroying situation. Seeking an explanation, she opens a history book and learns to her horror that “in 1859, when Oregon joined the union, it was the only state to explicitly ban all black people.” “The legacy of racism,” she concludes, “casts a long shadow.” Spot on, there.

Bad news keeps coming. The cliches don’t bring much comfort. The COVID-19 pandemic blooms, sickly, and she is astonished that, no matter how bad things might get, no matter how many people, old and young, may needlessly die, she and her family will not benefit from any sort of generally affordable, accessible, public health care because no such care has ever existed here and there is no sign of it coming to a neighborhood clinic any time soon. What happens if she, her husband, or her daughter, or any combination thereof, gets sick? How will they pay for that? She and her husband are gig economy workers. This is a big concern.

The adverts are beginning to feel like part of a con job. The smiley faces with half closed eyes and joints hanging from their lips feel almost malevolent now. Peaceful protestors are gassed and beaten in the street by off-leash thugs dressed in police uniforms and blessed with the authority of law. A family friend, another journalist, attends one of these protests. He wears a brightly colored vest that clearly identifies him as a member of the press. He gets shot smack in the chest with a rubber bullet, nevertheless. If press-corps-issued, brightly colored vests can be so blithely ignored, is nothing sacred? What’s happening? What’s next? And more than smoke can emerge from the enclosing forests, she discovers. Right wing baby men drive steroidal-wheeled pickups into the city, waving weapons, looking for a fight. Not only are their politics objectionable, they are the outdoorsy types who do hunt. They can shoot a deer and “dress it” without puncturing the bladder. Even a little. And then they stick the severed head on the wall with pride.

“I decided I needed to leave over the election period,” Pires writes.

One pauses. You can do that? Leave? Just like that? Oh yes, indeed. She and her family, reversing the Brexit course, leave all the way back to the UK where, as of this moment, they are currently waiting for the moment to play out, watching with the sense of having gone native, sort of. They are back home, made comfortable by the knowledge that it is a national scandal when a member of the government breaks lockdown rules. Where, according to The Guardian, Taylor Wimpey, a house building company, “expects bigger profits after the stamp duty holiday.” Huzzah for ye olde Taylor Wimpey, then. As the author puts it: “I am physically and mentally relieved to be distanced from white supremacists carrying guns on the streets, the threat of pandemic-related medical debt, and the specific cruelty of the Trump administration. We have a return ticket booked; we just have to decide if we’ll use it.”

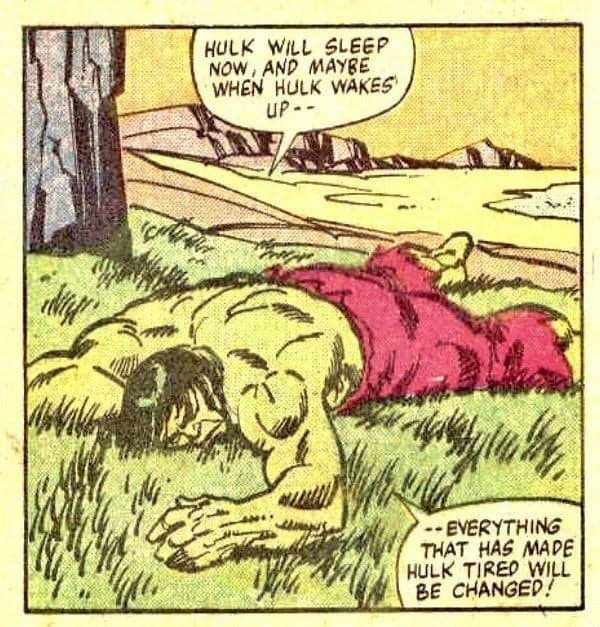

So, like you, Mr. Hulk, Ms. Pires is waiting for the news.

As promised: the bad, to start.

Come the day after, little of what exhausted and demoralized you has changed. Trump is going, going, we think, gone: but with 71 million, almost half of the country’s, votes stuffed in his pockets. The racism, nativism, misogyny, and the authoritarian style he represented live on. His folks probably don’t even need to go underground. He tweets, rages, and lies to a chorus of joyous war whoops, and the leaders of his party do not see fit to tell him to knock it off. Biden and Harris won, and Harris made history, yes, but the hellish parts of history are stubborn and there are some graves, no matter how old, that always feel as if they have been freshly dug. Such things ”cast a long shadow” as the wearied and wearying phrase goes. The Oregon State Constitution of 1857 cannot be rewritten. Portland itself, as historian and activist Walidah Imarisha puts it, will go on being a place that “…has, in many ways, perfected neoliberal racism.” The city, Imarisha predicts, will remain outwardly politically progressive while continuing to facilitate white dominance in business, housing, and culture.

The maddening contradictions will continue to madden. Harm will continue to come of them.

Now, finally, the good news.

Looking back on her foray into that vast wilderness of signs and symbols, Pires, on a positive and resolutely off-the-shelf note all the way to the bitter end, writes that America, in its very extremity, has an up side. “What I love most about living in America,” she writes, “is the feeling of possibility. Get in your car and you can drive for days through deserts, ghost towns, canyons, glaciers. We’ve spotted brown bears and bald eagles, driven around tornadoes, spent eight straight hours gripped to the wheel on icy snow. And in general, I find people less judgmental and cynical than in the UK.”

True enough. All of it. But that’s still not the good news.

The good news is that she, and her–only briefly?–adopted country dodged a real, not a rubber, bullet. She watched a country march up to the edge of a precipice while holding a gun to its own head. When it looked down, it saw that once one pulls the trigger and starts falling in a place like this one might never stop falling. Seeing this, it stepped back and dropped the gun. It is an unusual, albeit painful, bit of luck to meet one’s demons in the great wide open and yet not be destroyed, entirely, by them. A hue and cry was raised and was thankfully heeded. A rare chance for reckoning presents itself. Now let’s make some use of this knowledge, we shaken innocents, so that we might never be so naive ever, ever, ever again. Keep those eyes on the fool’s finger, which–like the dog to its vomit and the pig to its mire–will surely, some day, go wandering back to the fire.