Two Tales of National Redemption

On one side of the splitscreen plays, some people say, one of the greatest stories ever told. A band of pilgrims wanders the desert wilderness of the American West, maybe the Mojave. The brilliant light of the afternoon sun–punishing, ecstatic, purifying– floods the ready metaphorics of the landscape. Out of the unrelenting desert sands, they seek the salvation of their souls, but also their families, their faith, and their tribe. The path they wander is so parched, and they are terribly thirsty for the hereafter. A spartan camera crew documents the journey.

A once-in-a-lifetime weather phenomenon takes place the very day they start filming. The heat dome passes over the entirety of the west, taking the already-blistering desert heat to inhuman reaches of the thermometer. It nearly overwhelms the cast, crew, and extras. Some small, prickly shrubs along the desert path combust spontaneously. The cameraman is stunned by the manifestation but captures the moment for posterity nonetheless. This is, he thinks, practically a documentary of the Book of Revelations. His bosses at Mission Films, he thinks, are going to absolutely freakin’ lose their marbles over this.

The cast is disoriented by the heat, their thoughts disorganized, and some begin stumbling, become nauseous and lose their balance. The oasis they seek may be just around the next bend, they are sure they will find it, and they will drink miraculous water and be revived and witness the exalted end of all earthly things. How they will capture that moment on film is not yet a question the director has pondered, since the heat is affecting his judgment, too. But that doesn’t seem to trouble him. His gaze remains fixed upon that transporting moment, imminent and exquisite. There and then, no one will overcomplicate the natural order of the strictly gendered universe, nor the divine innocence of his children, nor the accumulation of his personal wealth. Each one a sign on earth of his virtue and worthiness.

On the other side of the splitscreen, an altogether different cast of characters prepares to march over the Alabama River, full of determination and belief in what is possible. The actors, both men and women, are properly dressed, for church in fact, because the scene takes place on a mid-twentieth century Sunday in the Southern United States. The costume designer for the film studied historical photographs from local archives for the tiniest details of stitching and button placement.

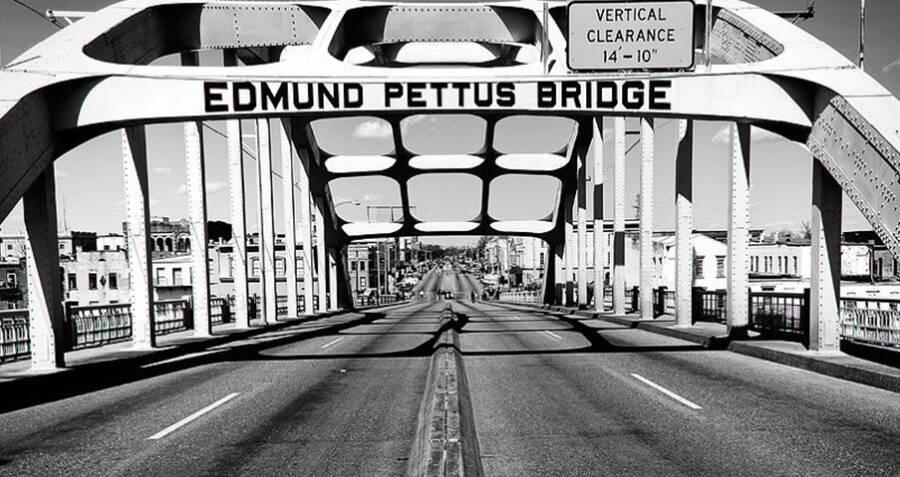

In this climactic scene, the ensemble cast begins their legendary walk from the Brown Chapel African Methodist Church to cross the river on a bridge named for a Confederate General, who once lived nearby and who, more than likely, without asking their consent, violently extricated the labor of their ancestors. The General fought a war to protect the practice of human enslavement, and when the Confederacy lost that bitter war, he packed his military jacket in mothballs for posterity and donned a different uniform, made of white bedsheets, a costume meant to terrorize and to silence.

When he signed onto the film, the director thought he was going to make a timely historical drama, inspired by uplifting biographies and historical research. But this movie, everyone on the set agrees, has become a horror film. The footage of the determined march across the bridge will be, in the editing suite, cut with palpably uncanny and brutal images, the resulting sequence a frightening montage: ghosts flashing and threatening, transposing past and present, haunting and riddling the future. That Bloody Sunday, in 1965, seemed like settled history just a short while ago, but the time and place of this bridge and all that it signifies has become unsettled and vexed once more. The actors walking across fully sense the menace and trauma in the landscape. They bravely make the crossing as if for the first time, for a second forgetting their craft and artifice. On the other side of the bridge lies safe public shelter, which will offer a few critical moments of privacy, wherein citizens might inscribe on uniformly printed ballots their consent as governed.

They’re back. 👊🏻