Who can confidently say what ignites a certain combination of words, causing them to explode in the mind? Who knows why certain notes of music are capable of stirring the listener deeply, though the same notes slightly rearranged are impotent?

E.B. White, The Elements of Style

Once upon a brightly cinematic morning, on a very muddy, overtrodden field of a family farm, to a mostly white, largely stoned, entirely disheveled audience, Jimi Hendrix played our national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Furiously. Electrically. And without words.

The dirt and the rain and maybe the cost of bus fare kept some people from gathering in this now legendary place, at that emblematic time, all of which has come, mythologically, to signify American counterculture itself. Some of those who were there left their ethnographic marks behind. We have audio recordings. We also have films, which were probably first projected onto sheets hung for home movie nights. Somewhat later, in more edited form, they screened in slightly more conventional arrangements, where people sat seated in rows in art houses at midnight. Later still, the footage took one more mediated step for public television, in a documentary series on the 1960s. The rest of us, decades downstream, we can find the performance via Google, digitized by a subsequent generation, and watch it on much smaller screens, wherever we happen to be, again and again, on YouTube.

At Woodstock on August 18, 1969, Hendrix played the national anthem as an instrumental, leaving behind the words that everyone already knows, mostly anyway. Francis Scott Key, the composer of the song, was a slave owner from Frederick, Maryland, who believed in the superiority of the white race and whose bad poetry glorified an otherwise insignificant battle in the War of 1812. Hendrix implies all of this in the understated irony of his performance and in his dissection of the idea that the love of one’s country is consummated with the act of war.

Hendrix played with casual virtuosity, reciting the familiar melody faithfully. And then, without warning, in the rocket’s red glare: a cacophony of sirens and reverb, arcing and descending, overdriven, the horrible sounds of bombing, the damages of war. And then, the melody of Taps, the song to accompany the funerals of dead American warriors. Just a phrase of Taps before Hendrix returns to the major melody, the one everyone knows, having taken this detour through a devastating landscape.

The story he tells winds around this question: what does it mean to die fighting in Vietnam? The question is too loud. It is too much. It sounds ugly. The performance is too loud, too much, too ugly. It is sublime. Tragic. A new kind of mourning.

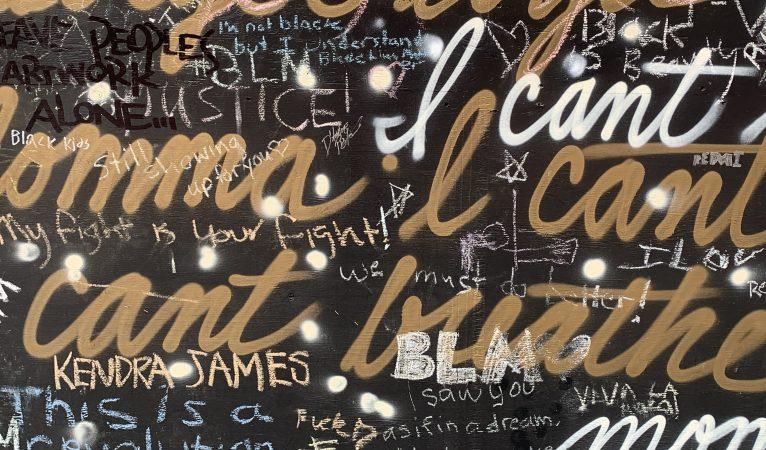

If you take a knee when our national anthem is played, are you showing disrespect to the flag? To our country? Or objecting in silence to the desecration of our society’s most closely held ideals?

Within the anthem as Hendrix played it, and in the ears of everyone who heard it, then and still: a wild discord. A fracture of our national narrative. Out of the dissonance cracks open fierce and buried tensions. Antagonism. Incivility.