Land of the free…where the legend will outlive you.

Neil Young, “Scenery”

Debra Martz, Mt. Rushmore, 2016

Stone Mountain, Georgia. Photographer Unknown.

To Gutzon Borglum, there was no contradiction. There was nothing to square. To him, all were great men of daring, of imagination, of fortitude. Descendants of Europeans, heralds of the triumph of Westen Civilization, and their conflict was, to him, merely indicative of their natural quests for primacy. And just as these warriors had struggled against a typically blindfolded world, so had he arm wrestled with art snobs who admitted his talent and yet sniffed that he had terrible taste in subjects and style.

George Washington. Thomas Jefferson. Teddy Roosevelt. Abraham Lincoln.

Jefferson Davies. Robert E. Lee. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. On their favorite horses: Blackjack, Traveller, and Little Sorrel.

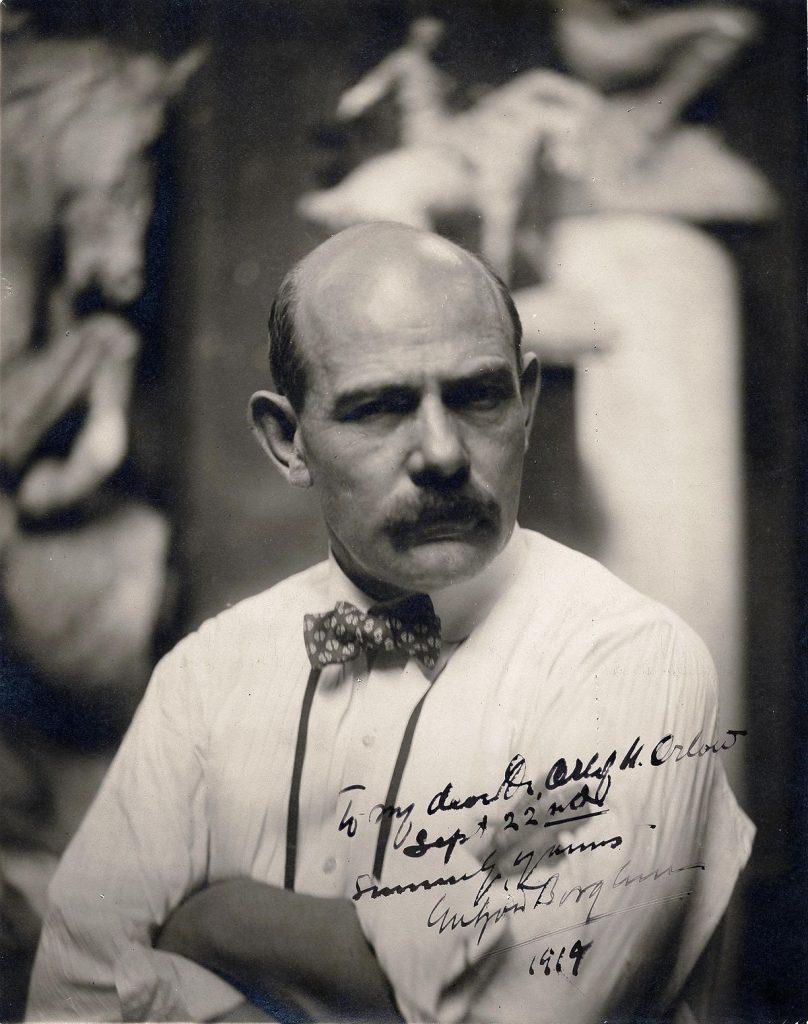

Borglum was no hereditary aristocrat. He spent most of his life in their company, though, pretending to be one, benefitting from the largesse and the cash. He was born in the Idaho Territory in 1867. His father was a Mormon woodcarver and part-time homeopath, recently immigrated from Denmark, who had two wives. His biological mother was banished from the paternal household when Gutzon was a baby. Graduating from high school, he became an apprentice in a machine shop. Although his gift for visual art was plain to see, had it not been for the attention of his teacher, Elizabeth Janes of Racine, Wisconsin, it is uncertain how this talent would have developed. Janes, nineteen years older than Borglum, was of considerable means and had studied art and music in Boston, New York, and Paris. Their meeting transformed Borglum’s life. They married and spent the next ten years travelling through Europe, studying art and exhibiting their work. Borglum was accepted as a student at the prestigious Académie Julian, where he became acquainted with Auguste Rodin, another former member of the working class. The Paris Salons of 1891 and 1892 accepted two of Borglum’s pieces. Returning to the United States, he was commissioned to sculpt figures for the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York, New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased one of his works, the first ever by a living American sculptor. He helped organize the era-defining New York Armory Show of 1913.

A long way from Idaho, he.

When Helen C. Plane, the wealthy President of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, suggested that he might carve a monument to the Confederacy at Stone Mountain, in Georgia, Borglum was ecstatic. The 300 million year old, 1,686 foot high dome of quartz monzonite spoke to him as no blank slate ever had. Here was raw material as substantial as his self esteem. It is unclear whether or not, in order to secure the gig, Borglum officially joined the Ku Klux Klan. The evidence is mixed. But to debate the detail misses the greater point. In the shadows of Stone Mountain, The Klan rekindled its movement and remade its rituals of terror, under the blank gaze of Confederate heroes. Borglum avidly endorsed this racist worldview and, through Plane, took its money. Klan-inspired, Klan-cash-infused, he carved a cliff side bas-relief, the largest of its kind in the world.

Describing the Klan’s attractions, the historian Linda Gordon lists many qualities that surely made Borglum swoon. To be affiliated with the Klan, “included the rewards of being an insider, of belonging to a community, of expressing and acting on resentments, of participating in drama, of feeling religiously and morally righteous, of turning a profit.”

The boy from Idaho had found a home, at last.

He had become, like Rodin, a de facto national sculptor. In 1925, the United States Mint, with the approval of Congress, issued a Stone Mountain commemorative silver half dollar to help fund the project. Borglum’s many other statues, celebrating various luminaries, some locally and some widely known, were raised in places as disparate as Portland, Oregon, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and Paris. He continued to be immune to the tensions that inhere in his projects and beliefs. He carved a memorial to Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, the Italian immigrant anarchists electrocuted for a crime they did not commit, while at the same time openly embraced the political philosophy Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, who imprisoned anarchists. Undisturbed by other incongruities, he wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt that he regarded “any and all forms of dependence or second place forced on our mothers, our wives or our daughters, as has been the history of men’s civilization…” to be an outrage. At the same time, elsewhere, he declared that he would “brush aside” any suggestion of adding Susan B. Anthony to the Rushmore sculpture “as I would an annoying fly on a wet day.”

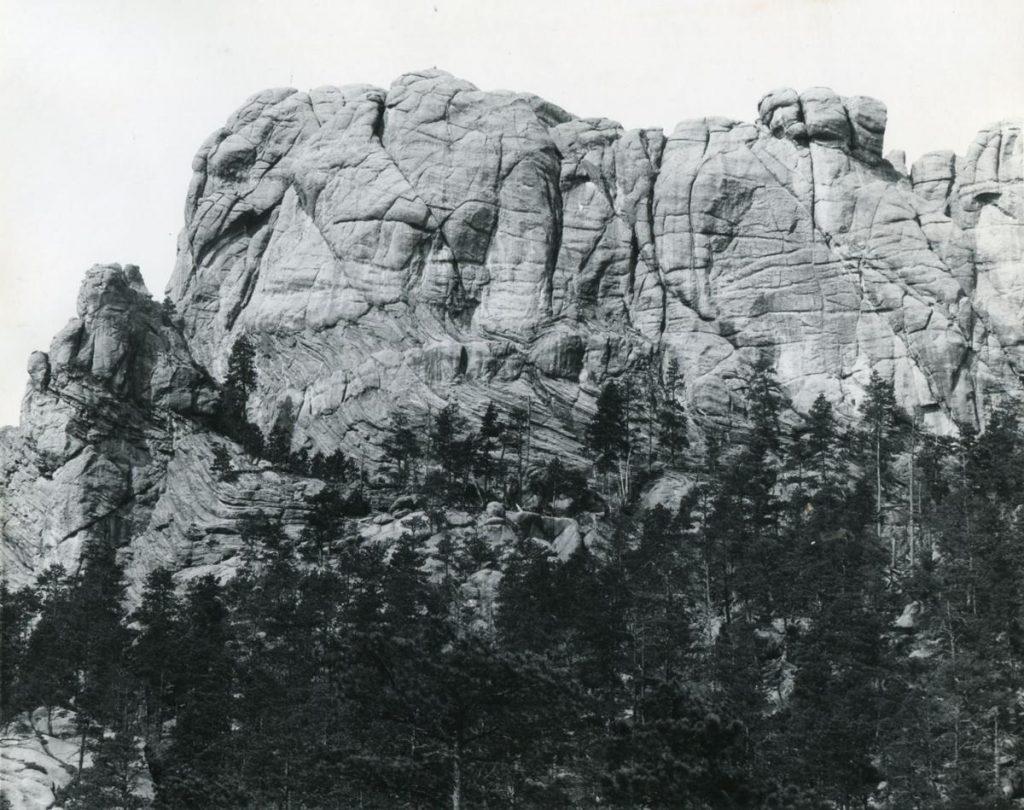

Black Hills/Mt. Rushmore, 1905, National Parks Service

The formation was made when batholic magma intruded into mica schist 1.6 billion years ago. Astrophysicists and geologists, mathematicians and paleontologists, toss around that kind of number all of the time. For the rest of us: too many zeros. What does such temporal excess mean? Or feel like? What to compare it to, to get some perspective? Using the relatively puny amount of time that people have walked around on Earth probably isn’t much of a standard of measurement. So what about dinosaurs? Could a Pterodactyl have used it as a launching pad? Dinosaurs first appeared on Earth between 243 and 233.23 million years ago. That means that the formation was already there for–the phone calculator won’t do for this one, you have to go online–one billion, three hundred fifty-seven million years. The big lizards showed up, passed by, vanished, and the scenery stayed the same. Taking a dinosaur as a hazy point of reference doesn’t work well either, then.

What about bugs? There must have been bugs before dinosaurs.

But so what if there were? How does thinking about bugs help one come to terms with this kind of enormity?

Suspicion grows. “Come to terms?” What terms are those, exactly?

Photos from the archives of Lou del Bianco, grandson of Borglum’s chief carver, and the Omaha World Herald.

Giving things names. This very basic premise of words is at once Edenic and agonistic. Black Elk, the Lakota Sioux visionary, called the formation Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe, or “The Six Grandfathers.” To Black Elk, the half dozen presences, simultaneously visible and invisible in the colossal mass of granite, represented the literal and spiritual directions of west, east, north, south, above and below. As imposing as the Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe were, though, Black Elk also knew they were only a small part of a larger, even more imposing range known as Pahá Sápa, or the “Black Hills,” so named because the pine covered hills looked black at a distance.

More names. The “Great Sioux Reservation,” which included the entirety of the hills within its boundaries, was created in 1868 as a result of a treaty entered into by the United States of America and several indigenous tribes. Signatories to the treaty included Lieutenant General William Tecumseh Sherman, sometimes known as “the first modern general” for his scorched-earth strategy in the Civil War, and Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, or “Sitting Bull,” who was sometimes known as Húŋkešni, or “Slow,” because of his purposeful and deliberative manner.

Following the discovery of gold, the United States of America, tossing the treaty away, seized the Black Hills. This double-dealing sparked the Great Sioux War of 1876, a conflict in which General George Armstrong Custer hoped to distinguish himself and thus advance his presidential ambitions. Those ambitions came to an unexpected end at “The Battle of the Little Bighorn,” also known as “Custer’s Last Stand” and, according to the Lakota Sioux, “The Battle of Greasy Grass.”

Despite this military blunder, citizens of the United States continued to displace the native population. By 1880, local gold mines were yielding four million dollars, and silver mines three million dollars, per annum. In 1884, Sitting Bull, who was eventually defeated in war, became a featured player in the “wild west show” put on by the master impresario Buffalo Bill Cody. Sitting Bull is said to have sometimes cursed audiences in Lakota while riding around the circus-like ring. Compensated for his performances, he gave most of his money away to homeless beggars, before being killed during his arrest by Bureau of Indian Affairs police.

In 1885, Charles Edward Rushmore, a wealthy lawyer and businessman from Tuxedo Park, New York, made the first of many trips to the Black Hills, where he enjoyed long afternoons hunting and fishing. The name “Six Grandfathers” that the Lakota Sioux had given these hills had not entered the idiom of more recent immigrants. Rushmore thought that the imposing bluff had no name and joked that it should therefore be named after him. In 1925, he donated 5,000 dollars toward the creation of a sculpture which was to feature the cliffside likenesses of selected American presidents. Striking pickaxe against stone, Borglum began work on October 4, 1927.

He liked to have his photograph taken, particularly when he could strike a pose overseeing the work at Mount Rushmore. While Luigi del Bianco, an Italian immigrant, supervised and performed most of the actual carving, Borglum made sure to stand next to any celebrity–like the silent movie cowboy William S. Hart–who happened by for a look-see. Here he was, side by side with pop royalty: Borglum, the artist for the ages. He was no faint-hearted aesthete wilting on a couch in a bouquet-decorated atelier in Paris. Au contraire. He stood on his own two feet. His art required dynamite and pneumatic jackhammers. He was drenched in sweat and sunburned. The dust of four hundred and fifty thousand tons of blasted rock rose at his command into the sky. He risked his very life when he placed himself in a leather harness, swinging out into the great wide open, coming face to face with giants.

Borglum with “Aviator,” date and photographer unknown. Studio Portrait, photographer unknown, 1919.