This is what I am: watching the spider rebuild - "patiently", they say, but I recognise in her impatience - my own- the passion to make and make again where such unmaking reigns --Adrienne Rich, The Dream of a Common Language

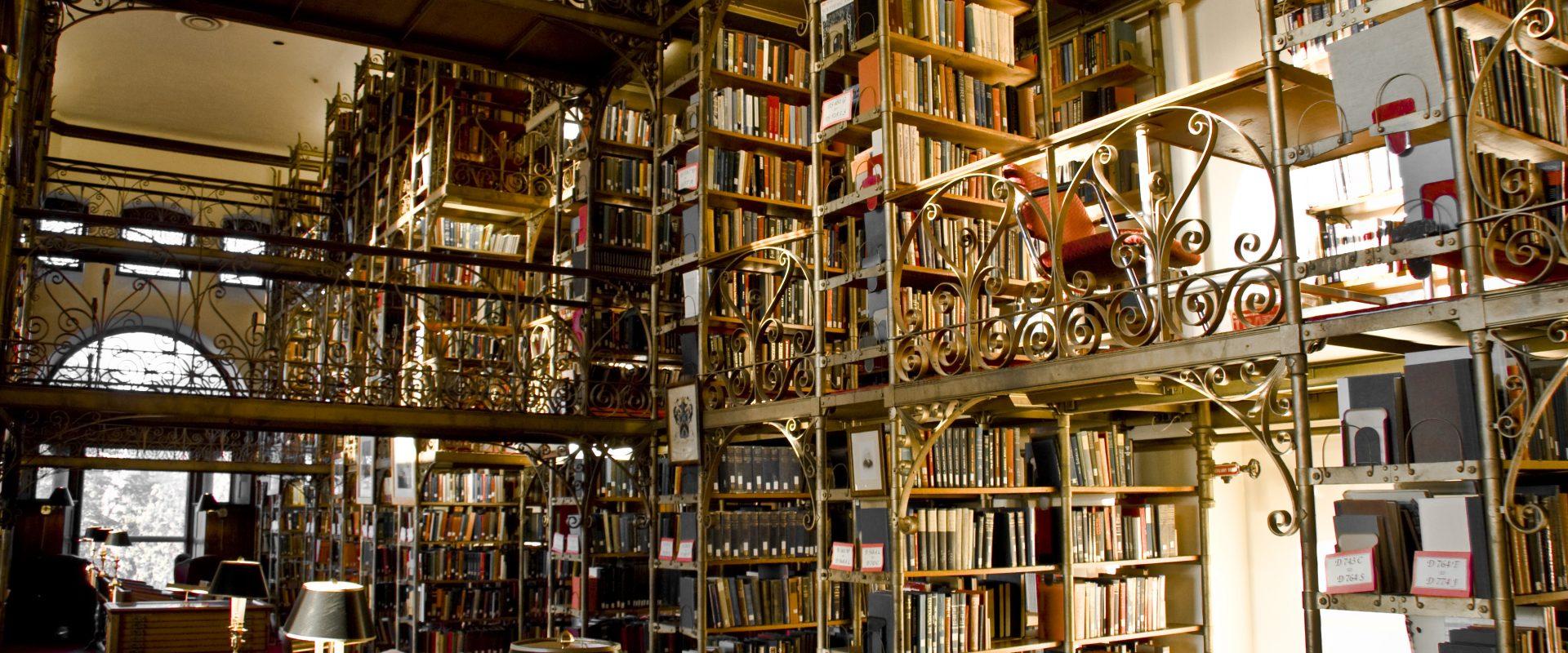

William Strunk, Jr. allowed himself a few moments to browse the three-story book stacks before he settled down to study. He had already staked claim for the evening at one of the long tables that bisect the main floor of the Andrew Dickson White library at Cornell University. So many new volumes had been recently added to the collection by the library’s benefactor and namesake, across every discipline he knew of, in every literary genre he could name, written in as many languages as he could count. It seemed to young Will Strunk that the building itself whispered puzzles and promises to anyone who cracked their books at these tables, lit by lamps placed at just-right intervals, like commas separating the clauses of a sentence. As he meandered among the books, across ornate, ironcast catwalks between towers, he wondered whether these shelves contained the elusive book he wanted most to read, the book he truly needed to teach the pencil-biters in his introductory English class, each one a unique mangler of the English language. Will, as his most famous student came to call him, was one of those people who loved sentences and all of the near-infinite ways they could be assembled. And yes, it must be said that he was also one of those people who could look askance at the verbal habits of others. And with this uniquely grammatical spirit, young Will Strunk longed for a manual of common English usage, a volume that he could not find on the shelves of Andrew Dickson White Library at Cornell University, or anywhere else.

And so having completed his graduate studies in English and taken his place among the Cornell professoriate, William Strunk, Jr. in 1918 wrote and published that longed-for book himself. 45 pages long, with rectangular, cardboard covers, full of Sergeant Strunk directives: omit needless words, use the active voice, make words tell. It could be purchased at the university bookstore for a quarter.

The library’s architect William Henry Miller had a talent for ceremony and so the Cornell library was likely designed with theatricality in mind. Miller was highly sought after on the east coast and had by the late nineteenth century built banks (cue: here and now reliability), churches (see: otherworldly awe) and mansions (acknowledge: the personal fabulousness of the resident within). Miller’s work was considered sufficiently scenic to suit Irene Castle, a modish silent movie star whose very name was an architect’s dream. She popularized the foxtrot dance step and the bob hairstyle and appeared in 1917 as the cliff-hanging heroine of Patria, a William Randolph Hearst funded serial advocating for war with Japan, a conceit born of the latest conspiracy theory concocted in the mind of the media magnate.

The library’s benefactor Andrew Dickson White (no relation to E.B.) was a sober, civic-minded fellow. A lifelong educational activist, with Ezra Cornell, he co-founded Cornell University in 1865. Appointed as its first president, he then oversaw the construction of buildings and the design of the campus, recruited faculty members and charted courses of study. Having amassed a vast, private collection of books, which included over 30,000 volumes, the collection was considered, of its kind, to be among the finest in the world. White donated all of them to the university, thus prompting Miller to the architectural drawing board.

White’s motives for placing his collection in the public sphere were not at all theatrical, which may have, in hindsight, put him at odds with his embellishing builder. In his view, the library was where you got work done. White prized replicable results over abstract speculation. A book, first and foremost, White believed, was a thing to be used. As tangible as any map, compass, or telescope, it was an instrument that provided a way of venturing into the epistemic unknown without getting hopelessly lost. White further believed that the worth of a tool gathers in proportion to the degree of its utility, to the frequency that it is used. The more often and widely it is used, the more significant, the more itself, the tool becomes. To this end, unique for the time, everyone at the university, not just upper graduates and faculty, was allowed to browse in and borrow from the library. With the installation of electricity, it was open and lit, again uniquely, for twelve hours a day. And the purpose of the whole bibliographic undertaking was not to merely provide Grade A reading material for a lending-privileged fraternity that assembled in gorgeous chambers at odd hours on a land grant allotment in upstate New York. The library’s books would become all the more significant, would become all the more themselves, if they could circulate, if they would have palpable influence in the wider, weirder, un-curated world that lay beyond the campus.

“I would found an institution where any person can find any instruction in any study,” declared Ezra Cornell, charting high-minded course for the university he would co-found with White. The sentiment inspires. The grandiosity invites skepticism. Did Cornell really mean any person? Perhaps he meant it in the Jeffersonian sense, in the way that the phrase “all men are created equal” also tolerated an economy buttressed by slavery, a founding contradiction that embattles our sense of American self-knowledge still. He made the statement in 1865, after all, when the definition of a “person” remained horrifically unsettled.

But in fact the historical record demonstrates that Cornell aspired to implement the notion in an entirely genuine, straightforward sense. In 1867, for example, he stated that “girls” should be “educated in the university as well as boys” so that “they might have the same opportunity to become wise and useful to society as the boys are.” Women began attending Cornell three years later, and Emma Sheffield Eastman was the first woman to graduate in 1873. In 1874, White encouraged the admission of African American students, “even if all our 500 white students were to ask for dismissal on that account.” In 1890, George Washington Fields, a former slave, became the first African American to graduate from Cornell Law School. Selected, outlying examples, of course, do not demonstrate that the institution was necessarily without prejudice. The ivied university would remain a club for the bigoted and the wealthy long after Cornell had established these benchmarks. Nevertheless, the ideal had been unequivocally stated and the slow, erratic expansion toward a more inclusive American norm had been charted.

Many doubted Cornell’s expansive new sense of the university. How would this uncommon gathering of students, each one studying a far-flung subject, come together in common pursuit? Cornell’s answer to this vexing question: All students, studying any and every discipline and its unique methods, would employ the same general principles of learning. The university would be a place “where truth shall be sought for truth’s sake, not stretched or cut exactly to fit Revealed Religion.” The pursuit of knowledge must be free from any kind of dogma, any type of unsupported preconception whatsoever, sacred or profane. Knowledge would advance as a result of direct observation, of corroboration, of consensus among enlightened equals, all of whom would have the same unfettered access to the same information. The university would thus encourage the freest possible forms of inquiry.

It’s not something you’re likely to read front to back. You flip through it, skip around in it. Glance at the afterword first and then maybe the introduction. The middle is full of off-putting grammatical nomenclature. The pronominal possessive. The appositive. The split infinitive. To soften the blow, some peculiar characters usher forth from the wings to illustrate these grammatical lessons.

Marjorie’s husband, Colonel Nelson, pays a visit. Horace Fulsome, Ph.D., presides. Uncle Bert, being slightly deaf, moves forward. Virgil Soames is the winning candidate. Polly loves cakes. Mary, our oldest daughter, sings.

Who are these fusty people?

Elwyn Brooks White smiles at the memory, Will’s “little book” and its cardboard covers. It’s somewhere here, the first edition, he’s certain it must be, hiding between other lightly foxed, cloth-bound volumes. The library has seen so many actual and allegorical seasons, for him and countless others who have traipsed these catwalks. It has become a shrine of sorts, and yet still useful, and also flooded with nostalgia. Here in the third floor stacks of the Cornell University Library, where he studied every night as a student almost three decades ago, E.B. White steadies himself in these undertows of memory, in the countercurrents of utility and nostalgia.

It is 1957, and E.B. White is taking another look at his Professor’s manual of usage. Now an immensely successful writer, E.B. has had a regular column in the New Yorker for years and has written and published two extraordinarily popular, well loved children’s books, Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little. The publishing house McMillan has commissioned White to revise The Elements of Style for both the college market and for the general book trade. Perhaps the book has become something of a curiosity, he wonders. Is the little book now nothing more than an old-school box of relics, a detailed illustration of a dying style? Or is it still entirely relevant, just in need of dusting off, a fresh approach?

He has an idea, yes. He will renew the passion for impeccable usage that inspired his Professor’s project. But he will extend the book to encompass the more elastic theme of style, advice drawn from the writer’s experience of writing, sustaining Strunk’s deep sympathy for the reader, a man floundering in the swamp. It was the duty of anyone attempting to write English to drain this swamp quickly and get his man on dry ground, or at least to throw him a rope.

Virgil Soames, the candidate who eventually wins, makes a campaign promise. Virgil says that he, too, like many before him, is going to roll up his sleeves, snap his suspenders and drain the swamp. By this the candidate means that he will empty the government of elite influence, of corruption, of nepotism. Virgil wins his election and does the opposite.

Yes, White thinks, I will most definitely hold onto this, this concern for the bewildered reader.

Still in print, legible onscreen and in your hand, the humble case set forth on behalf of plain writing has not been and probably cannot be improved upon. Be clear. Use the active voice. Omit needless words. Express coordinate ideas in similar form. Use definite, specific, concrete language. Avoid tame, colorless, hesitating, non-committal language. Vigorous writing is concise. E.B. pauses for a moment to marvel at exactly how enduring these commands, at once austere and loving, have proven to be.

The Elements of Style eventually sells over ten million copies.

Without mentioning it, the book also speaks to a more fundamental, essentially American assumption about the plain style in particular and the purpose of language in general. To use the plain style is not to celebrate plainness for the mere sake of plainness. Instead, to use plain language reflects a tacit recognition that language is not, in and of itself, necessarily plain. Language can confuse, obfuscate, and blur just as easily, perhaps even more easily, than it can clarify. At the same time, if used with exacting precision, according to principles of common usage, it can help dissipate our natural capacity for error and confusion and our thrall for pretense and illusion.