“The Sheriff of Maricopa County”

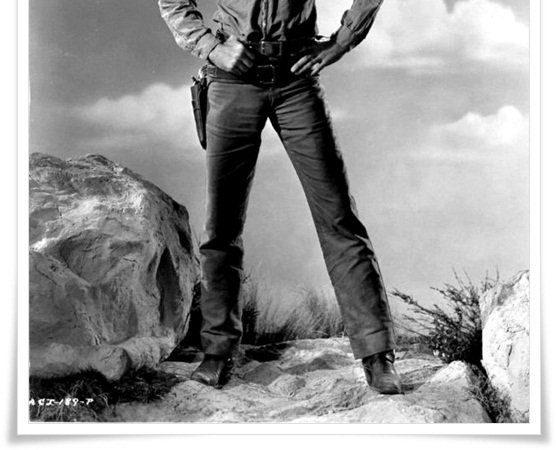

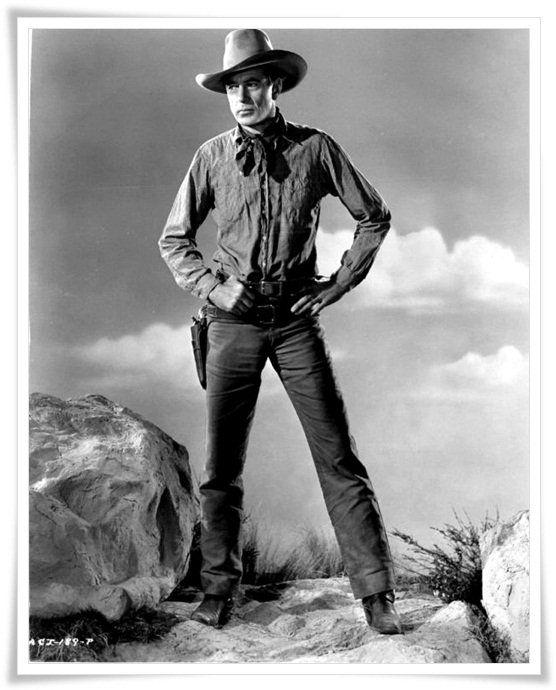

What passes for identity in America is a series of myths about one’s heroic ancestors. It’s astounding to me, for example, that so many people really appear to believe that the country was founded by a band of heroes who wanted to be free. That happens not to be true. What happened was that some people left Europe because they couldn’t stay there any longer and had to go someplace else to make it. That’s all. They were hungry, they were poor, they were convicts. Those who were making it in England, for example, did not get on the Mayflower. That’s how the country was settled. Not by Gary Cooper. Yet we have a whole race of people, a whole republic, who believe the myths to the point where even today they select political representatives, as far as I can tell, by how closely they resemble Gary Cooper.

James Baldwin, “A Talk to Teachers” (1963)

Setting: Maricopa County, Arizona. Arizona joins the union on February 14, 1912, the last state to fill in, patchwork style, the contiguous American “lower forty eight.” Most of the Navajo Nation lives here. Arizona is also populated with many Spanish-speakers and their descendants, long-ago colonists who came from places like Aragon and Catalonia, Castilla and La Mancha, Extremadura and Galicia.

Stage Direction: On a darkened sound stage, the crunch of heavy footsteps, leather boots grind into parched desert earth and pebbles that might otherwise burn the skin. After a count of a dozen or so steps, an elderly male figure becomes visible in gradually increasing light, his slow gait marching in sync with the pre-recorded audio.

Enter: Sheriff Joseph Michael Arpaio.

Sound: His voice, speaking:

I always loved the movie house because I saw all the westerns. I really liked a cowboy movie and that was my first contact with a sheriff. I never realized that in 1992, I would become sheriff, that I would be a sheriff. And to me it is a great honor.

Named for the patron saint of workers, he is born in Springfield, Massachusetts on June 14, 1932, a day also known as “Flag Day.” According to the story he tells, his parents came to the United States from the region of Campania, Italy, passing through Ellis Island, the legendary point of entry to the United States that lies just beneath the Statue of Liberty’s uplifted torch.

His mother and father would have been subjected to various indignities on the island: inspections of eyes, skin, nails, and hair, searches for fungal infection, nitpicking about undesirable political affiliations, suspicions of dimwittedness, and quizzes in a language they do not fully understand. He does not describe this. He does not mention how they, as Italians, are naturally expected to live in certain carefully circumscribed neighborhoods or about how, not so long before they arrived in New York Harbor, eleven Italian immigrants were lynched in New Orleans in 1891 by a mob, having been accused of crimes none of them had committed.

His mother, he says, dies as a result of his birth. He is raised, he says, by his father. He works as a delivery boy at his father’s grocery store. Springfield, Massachusetts, at the time, is a prosperous but otherwise unremarkable New England town. The Smith and Wesson factory manufactures guns there. Down the street, the Milton Bradley factory manufactures board games. Theodor Geisel is born there, too, takes art classes in high school, and later becomes “Doctor Seuss.” Joseph graduates from high school and joins the army. He joins the Washington, D.C., police department. He joins the Las Vegas, Nevada, police department. He joins the Federal Drug Enforcement Administration. He retires from government work and joins the race for the office of Sheriff of Maricopa County in 1993.

He wins. And thrives in the job. Comes into his own, even. The faceless, buttoned-down, behind-the-scenes life is over. The New England grocery boy is born again in the brilliant light of public life, in the American West, in the zone of news cycle politics. At his zenith, he is the most popular politician in the state.

He remains in office, defeating all opponents, for the next twenty one years.

How did he suddenly rise, so metamorphosed, from nowhere, from the empty scrub-ground and the wide avenues of Phoenix?

“They call me a media hound,” he says, “and that might be true.”

He publishes a book about his personal “war on crime,” portraying himself as “America’s toughest sheriff.” Rush Limbaugh likes the book. A lot. Thumbs up. Joe publishes another book: Joe’s Law. This one is about drugs, border security, and “everything else that threatens America.” Notably, the book’s ghost writer uses the word “law” in the possessive sense. It’s all his, it’s all Joe’s, law, you see. He is the magical singularity who speaks the unalloyed truth on NPR, on CNN, on the BBC, and who strolls down the Hollywood Walk of Fame, walking over stars laid in concrete.

In the jail he runs, inmates wear pink underwear as a form of communal humiliation.

He hands out autographed pairs of pink underwear to crowds.

When they wear pink underwear, the inmates acknowledge that they have been personally branded by Sheriff Joe.

It’s his trademark.

Crowds joyfully receive the autographed, souvenir underwear he peddles.

The schtick works. The lariat trick enthralls.

The map to the wilderness is found.

Joseph Michael Arpaio has become “Sheriff Joe.”

He has a complete handle on both his image and his acts.

“I know just how far I can go,” he says.

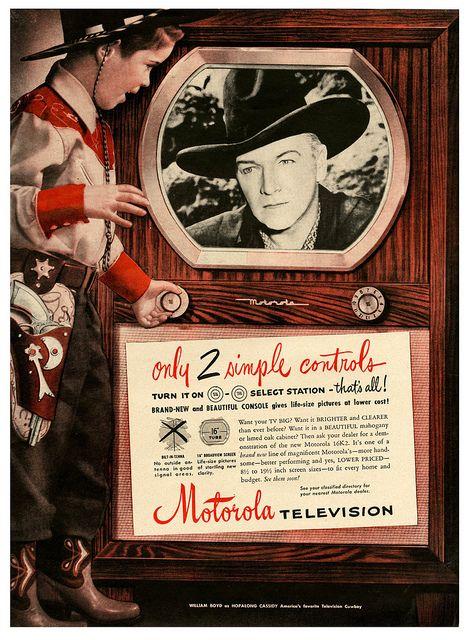

Hopalong Cassidy

Gary Cooper

Many heroic actions and chivalrous adventures are related of me which exist only in the regions of fancy.

Daniel Boone

Accompanied by his daughters Diane and Sharon, Walt Disney wanders through various American amusement parks. It is the late 1940s. The polymathic, master impresario of nostalghia from Chicago lives at the apogee of the American century, knows it, and wants the world to know it too. He pulls another Lucky Strike from a suit jacket pocket. The girls eat ice cream cones. He wanders and smokes. He doesn’t like what he sees. He is disheartened. Wooden, rattle-bone “thrill” rides. “Haunted” houses. Tunnels of “love.” So dumb and deadening. We can do better than this.

He imagines a new sort of pleasure garden. One where one can stroll through both the present and the past. It will be a happy and consciously didactic garden, he thinks. One to be enjoyed by both the young and young at heart.

The Magic Kingdom opens in 1955. It is segregated into precisely demarcated “lands,” each with its own theme. In “Frontierland” a paddle-wheel river boat carries you down a manmade river past a settler’s cabin set ablaze by savages to a shooting arcade where you can try your best to blast faux-whiskey bottles to pieces. Afterwards, you might like to toss back a sasparilla and wipe your mouth on your sleeve in satisfaction at the “Golden Horseshoe Saloon.”

Just like in the movies.

Sort of.

That same year, Disney promotes his new television series about David, better known as “Davy”, Crockett. Disney is glossing and riffing on the life of a military and political adventurer born in Tennessee in 1786 and killed during the Battle of the Alamo in 1836. The “Crockett” image precisely embodies Disney’s ideal of the cheerful, rambunctious, American folk hero. Disney decides that children, like Diane and Sharon, should become more “Crockett conscious.” Polyester caps, modelled on the raccoon skin cap allegedly favored by Crockett himself, are marketed at “trading posts” in the magic kingdom and beyond.

The fad catches on, nationwide.

“Frontierland.” A bounded world, measured by the acre, located inside a physical amusement park to which admission is charged. And, at the same time, a free, limitless-feeling headspace, allegedly open to anyone who possesses sufficient grit and imagination. Ladies and gentlemen. Boys and girls. Step right up. Even if you live in one of those no-elbow-room-cities where kids splash in streams from opened fire hydrants on sweltering summer afternoons instead of skinny dipping down at the swimming hole. Even if you sway underground on the “D” train rather than high in the saddle and can barely spot a single star when you stand outside on the fire escape at night, “The William Tell Overture” and the Lone Ranger’s voice still crackle from inside the Philco. You can still tilt the tube’s rabbit ears just right and watch the figments assemble out of the static. Rowdy Yates. Matt Dillon. Little Joe. The stars you can’t see in the light-polluted sky are shining right here, in the living room. Put away your pretend, homemade telescope made from the cardboard tube from inside a roll of paper towels and that you covered with aluminum foil. You can’t see the man flying in the Mercury capsule up there, anyway. You can touch these faces, though, instead. Right here. Your fingers tingle, crackle a little, with a buzz of static electricity. With the buzz of grit. The buzz of imagination.

The West: an imaginary and an actual place.

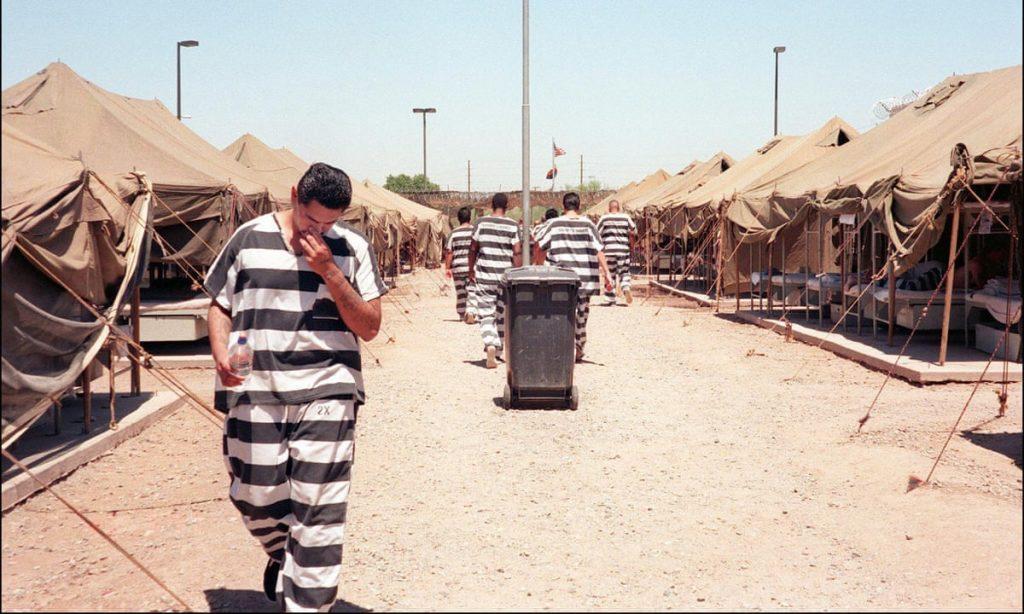

A few inmates at the Maricopa County Jail, strapped to a chair, get shocked to death with tasers. Presumably, they die while wearing pink underwear.

Sheriff Joe knows how far to take it. Which is pretty far, as it turns out.

It can’t all be pixie dust, you know. You have to produce tangible, hold-it-in-your-hand results, too.

You have to show that you know how to control both the image and the act.

Sheriff Joe orders checks for immigration status during routine traffic stops. He establishes a tent city jail surrounded by barbed wire. He refers to this as a “concentration camp.” He says he knows that the inmates call him “Hitler.” He is okay with that. Inmates–many of whom are pre-trial detainees who have not yet been found guilty of any crime–are exposed to temperatures, magnified by the enclosure the tents, as high as one hundred and thirty five degrees. Inmates are denied hydration and nutrition and shelter. By no accident, the tents are placed next to the town dump, the dog pound, and the waste-disposal plant. He hangs a neon “vacancy” sign high from a guard tower. He resurrects the old school chain-gang, and shackled inmates shuffle through empty lots and bury the indigent dead at the county cemetery.

“That’s where you’re going if you’re not good,” he says.

This is a good lesson to share with children, he says. He is famously reluctant to pursue reports of sexual assaults in neighborhoods known to be populated by undocumented immigrants.The message: if you are assaulted and live at a certain address, don’t bother calling Sheriff Joe. Drawing attention to your violation might even make things worse for you. And your family. Sheriff Joe never explicitly explains the jurisprudence behind this reluctance. As an action figure, any explanation coming from him is perforce unnecessary, but the logic is clear. You came here illegally. So don’t expect the law to be on your side now. You ignored that law. And now, I’m going to ignore this one.

Two deputy sheriffs decide to take a lunch break. They will be generous to themselves, they decide. An hour today? Maybe a little more? Turning the radio down, they drive up and stop at their favorite lunch counter, the one that shares a kitchen with La Tienda Latina in downtown Phoenix. They squint at the menu. The frijoles here are the best. The arroz con pollo can’t be beat. Lupe, the owner of the place, knows them well and instructs her daughter, Marisol, to give them extra portions. This one likes more beans, less rice. That one likes more rice, less beans. Marisol does as she has been instructed. While pouring extra sugar into cups of cafe con leche, Marisol looks away for a moment at the television propped up on a little platform in the corner of the room, where the wall and ceiling meet. The television is broadcasting a story about a big pile up involving a half dozen cars and a semi carrying propane tanks, out on Interstate 10.

While looking away, she accidently knocks over one of the too-sweet cups of coffee.

She wipes up the mess hurriedly with a bar towel and then rushes to the storage room for a fresh supply. While she is out of earshot, one of the deputies smiles and says to himself, wryly: “ethnic cleansing.” The other deputy smiles and says to himself, wryly: “make my day.”

The deputies have had one cup of coffee too many and each must take a gentlemanly trip to the restroom. And then, finished with their meal, they wipe their mouths, tip generously, and leave.

They pull out of the parking lot into traffic and reluctantly turn the radio back up. Dispatch instructs them to patrol a nearby neighborhood where a lot of working class, immigrant families live.

Their caffeine jitters come out as sweaty palms and, now, dreading what comes next, a wave of nausea. The frijoles that came with lunch, so tempting an hour ago, are rumbling.

It makes you want to bang your head against the dashboard. That neighborhood? Again? Why? They’ve already been to that neighborhood today. They started the day with an early morning cruise down those same streets, when Lupe and Marisol were probably turning on the lights in the storage rooms and in the kitchen, when the sun had not yet slid into view through the plate glass windows of La Tienda Latina. Already. That morning. They drove the street grid, up and down. They recorded the license plate numbers of old Toyota Tacomas parked at the side of the street in the predawn half-light, the pickups loaded in the back with sprinklers and soaker hoses and wheelbarrows, ready to go to Scottsdale, long before sprawling Scottsdale, by noon, will grow so unbearably hot. They drove the quieter streets and the busier streets, passing yards that front one-story bungalows scattered with toppled scooters and sun-evaporated splash pools and deflated soccer balls.

And they found nothing. Nothing but emptiness. Even the people seemed to have evaporated.

And now dispatch tells them to go back. Go back? For what?

Does dispatch think that we are going to find a bunch of illegals throwing shopping carts through a WalMart window? Or tatted Mexican dudes, with teardrops at the corner of every eye, on every street corner, selling crack to white kids?

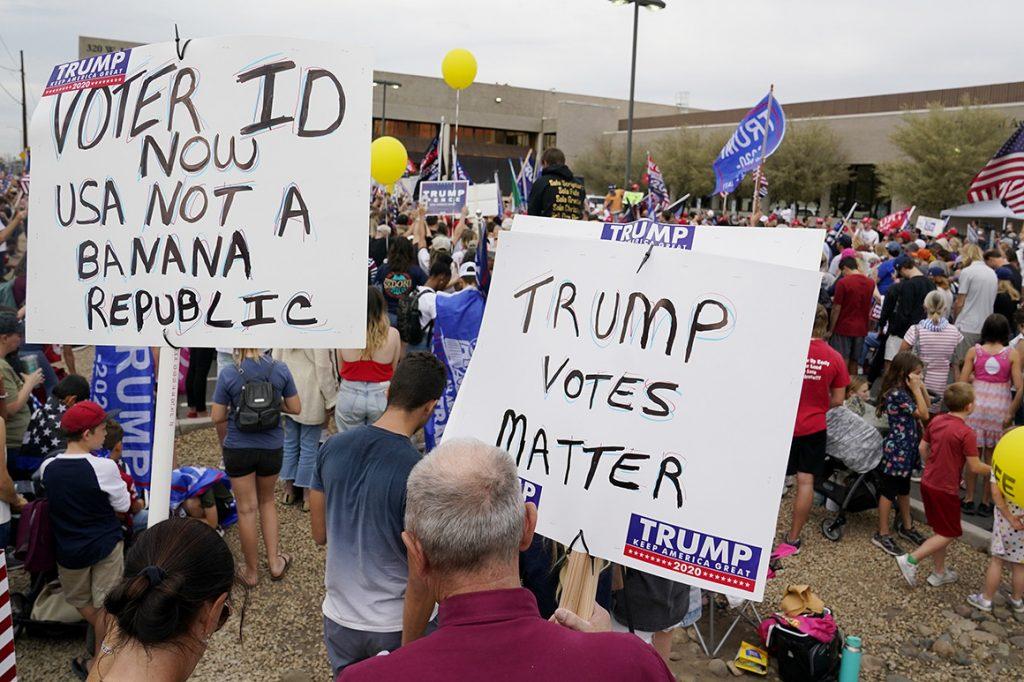

Or do they think that we will find the rag-tag remains of one of those messed up posses, armed and taunting, wrapped in American Flags and chanting outside the County Clerk’s Recording Office? Chanting and threatening, rifles and automatic weapons on the ready, demanding “COUNT THE VOTE, COUNT THE VOTE,” while the folks inside are quietly….counting the vote?

Is that what dispatch really thinks?

Of course not. The purpose of the return is clear. They are supposed to go back to that neighborhood and drive up and down those streets to make an impression. To create an image. To look tough. To frighten. To intimidate.

Dispatch knows that. And the people who live in the big houses of Wagonmaster Lane and Sunset Circle know that too.

Here’s a better idea.

Let’s go to back to Lupe’s, have a couple of Coronas, and say fuck it for a while.