It was inevitable, the doctor thinks. After going on and on about radical acceptance and unconditional love and agape and all of the rest of that sort of bullshit in those lectures and in those books and while chatting at those book signings and while yapping on that podcast and, probably worst of all, while sitting with a feed in his ear in front of that stupid, dead-eyed camera on that television program–and in spite of his own, sometimes painful self-work through which he has come to realize that he is still greatly fascinated by publicity and prostitutes–he has been presented with a patient whom he hates.

And he doesn’t know how to get rid of her.

There she sits, in the comfortable leather chair, very blondly, her feet up on a tasteful, matching leather cube, her hands resting in her lap, her head tilted at the ceiling, talking and freely releasing fresh wafts of her unspeakable perfume. For some reason, she always wears white, immaculately maintained, sneakers and pink topped sport socks, with little deedle balls at the heel, to the appointments, both of which she takes off as soon as she sits down, carefully placing one shoe and one sock next to another shoe and sock, keeping the set tidily tucked next to her chair. She says she needs to “let her tootsies out” in order to feel comfortable. Before she puts her shoes and socks back on near the end of the hour, she always takes out a little plastic bottle from her pocket and spritzed the insides of the shoes with what, one could only assume, is some kind of antibacterial, antifungal deodorant.

She wiggles her toes. He has a reflexive reaction. He should have a sign on his door: no shoes, no shirts, no service. But that would dig into the bottom line. So back at you, brother, he thinks. If you project hostility, it comes right back and then you are left with egg on your face. Metaphorically, of course. Sometimes an egg is just an egg.

His mind wandering, he looks outside, unafraid of breaking empathic eye contact with the patient, having learned–as an example of her sociopathy, frankly–that eye contact and empathy are not her strong suits.

It is a matter of ethics, he knows. Of exercising professional judgment. Really hating your patient is an obvious sign of negative countertransference. He tells himself that he should be able to handle such a wrinkle. And yet, he recoils in the moments before she arrives, finds himself closing off, steeling himself against her. How to square this hostility with the work of his lifetime?

She said that she had put her life in his hands.

It’s a dilemma. He feels trapped. He sought out the advice of his colleagues at the clinic. Dr. Dickinson offered the first perspective: allow her to break whatever expectations you have of her, know that she will perceive your attempts to contain her and know that she will react. She will perceive it as an incitement, and it will derail you at every turn. Open your ears, wider than you think you have to, wider than ever you have had to do.

Dr. Burroughs, forever the cynic, the snark of the poker-face bunch, always alert to hypocrisy in the tide of self-interest, had different thought. Just what kind of fraud are you? he had intoned in his trademark, Midwestern drawl. Are you really going to ask her to put on her shoes? What are you afraid of, that she’ll quit, and you won’t get your fees, that you’ll actually catch a whiff of her feet?

He had caught a lot of flak, initially, for locating the clinic outside of Reykjavik. No one would show, a thousand haters howled. And it’s a nice place to visit, but who is going to set up shop and practice there? Fortunately, Dr. Smith had no qualms about the location, living as she did, for so many years, a recluse on the Jersey shore, writing poetry by hand in journals and composition books, which collected on bookshelves next to all of her Rimbaud translations. And as soon as Dr. Smith showed up, the floodgates opened. Now look. A waiting list a year long. A hotel in town that has an exclusive package for clients of the clinic, including pony rides out to the volcanoes, hot springs, and waterfalls. And even though some of the other clinicians–Dr. Burroughs in particular, of course–complained that they shouldn’t accept any more Medicaid patients as the reimbursement rates amounted, in Dr. Burrough’s words, to a stick up, everyone was, in fact, doing quite well, thank you.

And neither had the clinic become merely a trendy place for the rich and famous to get their heads shrunk. Yes, some of the patients were household names and came with a security detail, but their problems were real. The pain had consequences. Take this particular patient, for example. She is truly suffering, and her promising career in politics is jeopardized as a direct result of her paralyzing phobia. If one could, just for fifty minutes or so, and one can always cheat and cut it a little short, put one’s own politics aside–something that Dr. Pop, who believes in a theory of radical rejection, to be conducted shirtless and at high volume, and who insists that she is an agent sent to impose mental martial law on everyone, adamantly refused to do–you understood that, no matter how vile, she sees herself as a public servant.

And even more importantly: she is a human being.

She blows her nose, wads up the tissue, which she has kept in a clenched fist, and, grimacing, looks back at the ceiling, tears streaming from her eyes, her thick mascara streaking.

“And I know my mascara is probably running,” she hiccups like an injured child. “But I just don’t care. This time, I just don’t care.”

She takes several deep breaths.

“I’m being tested.” she said. “That’s how I have to think of it. I am in Gethsemane and this is my test. Do I choose the right path?”

“You’ve mentioned that place before. You can’t be serious. You can’t compare what happened there to–”

“Are you hard of hearing? Or what? I am in Gethsemane, dammit.”

I don’t know about you, lady, the doctor thinks. But right about now I’m being sorely tested too. In fact, you’re testing us all.

She has already burned through some of the finest clinicians he has on staff. Drs. Smith, Burroughs, and Pop, for example. She had found it “totally fucking impossible,” to use her words, to work with any of them. “I cannot even sit in a room with a drug addict, or a self-mutilator, or a woman who doesn’t always shave her armpits,” she announced.

This declaration of hers had prompted a vigorous debate as to whether he should, in fact, even take her on as a patient himself as “caving in to a thug and turning over the milk money,” as Dr. Burroughs put it, could well exacerbate her refractory borderline traits. Some discussion was then had regarding pairing her with Dr. Dickinson, but since the patient had absolutely no facility with nonliteral language–and because Dr. Dickinson was sometimes so nonliteral that even the other clinicians didn’t always know what she was talking about–a reluctant consensus was reached. All things considered, he was probably, just as she said herself, her “only hope.”

Outside, down in the harbor, a brightly painted little fishing boat headed out to sea.

Inside, she talks.

“Like I said,” she begins, raising her voice, getting the doctor’s attention back. “I’m a crossfit nut. Totally into it. You have to understand that part or none of this will make any sense to you. Because I just bet you’re not a crossfit freak like me.”

“Guilty as charged,” the doctor says, raising his hand.

“You should see me,” she enthuses. “I get to every session early. Boom. I am hitting it. Right between the boxes and bells I figure out my playlist. The other day I was thumbing through my iTunes list looking for some thrash, and somehow the theme music to Harry Potter launched–I downloaded it for my daughters–and over the speakers, it came on, and oh my god, I shut that shit down before anyone could hear it. Can you imagine? Cross-Fit Hermione? My reputation would be ruined. No way. I found my thrash and went straight to the speed. Metallica, Megadeath, you know, I like something with a little class, okay? What can I say? My WOD goes up on the white board. Warm-up for blood flow. Jumping jacks, box jumps, burpees, squats. Then onto the good stuff. Dead lifts and pull-up thrashing butterflies, alternating, AMRAP.”

“AMRAP? What’s–”

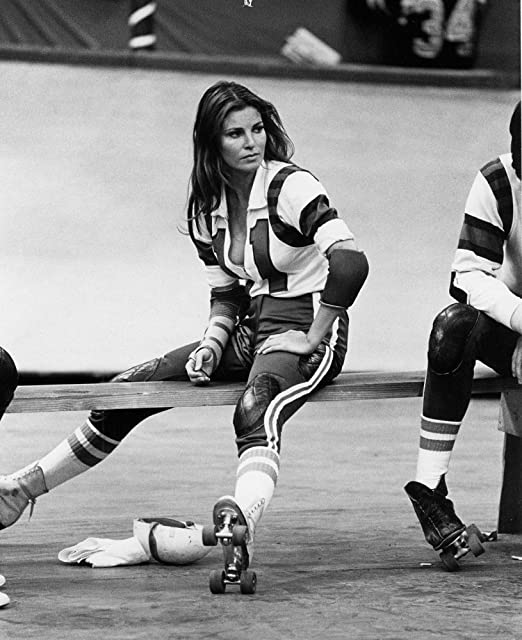

“Doesn’t matter. You wouldn’t get it. Anyhoo. I know when it started. I’m hitting it and I notice this woman. She’s new. Total machine. Killer playlist. Killer definition. I’m totally impressed. We head out to the floor at the same time and I tell her, like, wow, you are the bomb. She’s got these dreads stacked up on top of her head. Thinnest waist I have ever seen. Monster-power thighs. She told me that she skated for the Diesel Chicks, the Derby team. Everybody knows about the Diesel Chicks. Great merch, you know, lots of dyke fans. It’s almost a cult. I am guessing. Not my crowd.”

“Not your crowd,” the doctor repeats, reflects, back. “How would you know anything about those chicks?

“Right? The Diesel Chicks and me are like not happening. But this chick in particular is, like I said, she’s a crossfit bomb. I admired her, you know, as a colleauge. We end up totally by accident, total coincidence, doing clean-and-jerks. Like at the same exact time? How weird is that? Right? And even our timing, our rhythm is like the same. It’s like we’re doing it together. Like we’re each other’s personal trainer but like we’re the person who is being trained too. But no one says anything. It’s hard to describe.”

“You’re doing quite well, honestly.”

The patient pauses. Grits her teeth. Closes her eyes.

“Okay,” she says, after a deep breath. “Here comes the nightmare. I’m in a castle. But the castle is a school, too. It’s scary. But you want to be there, too. It’s like Hogwarts. But some people are naked. You can hear voices. It’s like people are reciting lessons and getting spanked somewhere or something. Everything smells like sweat but also like air freshener. I have to pee. All of a sudden. So I find the women’s restroom and the restroom is sort of a locker room, too. And Diesel Chick is there. She’s changing. She’s taking off her clothes, her street clothes, like she’s just come from an office or something. Her workout clothes are folded on the bench, her work clothes mostly off, half undressed, not yet dressed, and I am looking at her, and I am looking at the clothes, and I am looking at her powerful thighs, so much definition, so much bulk, bulging, my eyes draw to her pubic–and I see it, I see it, I see it–and Metallica is in my head, and the tiny room becomes too small for us and it starts spinning.”

The patient sobs. And also chokes, like she might be sick.

And now, in her real life, in her public life, as a weaponized and faith based political operative, she says, through sobs–having recited her struggle yet again without a trace of insight, the doctor notes–she swoons and sometimes even passes out whenever anyone uses the words: “public restroom.” Using a public restroom herself–even when she thinks of it as “the little girl’s room”–is out of the question. In fact, lately, she’s been having a hard time leaving her condo for fear of an encounter with a public restroom. With just those two terrible words. And now it’s even getting worse with all of the creeps out there trying to create not just public restrooms but ones that are gender neutral, nonbinary, fluid. She becomes frantic with anxiety at the verbal expanse, with those terrible thoughts, those frightening memories. If this gets any worse, her career is toast.

“Just imagine how often those words come up during one of the fundraising prayer breakfasts I have to attend.”

“They’re Christian prayer breakfasts you’re going to? Right?”

“Are there others?”

He tells her that doesn’t see how the subject of public restrooms has anything to do with a prayer breakfast. And he has attended a few himself, he points out.

“I don’t get it. I just don’t see the connection,” he says.

“Well, you wouldn’t.”

“Why not?”

“Because of who you are. You probably even can’t.”

The doctor grunts.

“You’re too good. You’re too loving to understand.”

He cringes. Inwardly cramps. He can’t stand that word. Loving.

“Please also recall, however,” he says, “that I urged selling one’s cloak and buying a sword so one could take up arms against–”

“You don’t even realize, you can’t even guess, what’s about to happen. To all of us.”

And now here comes the doctor’s nightmare. He dreads what comes next, most of all. He doesn’t want to hear about it. He finds his mind refusing what he is about to hear. What scares him, what really scares him, and what turns her into a public health menace, is the real power she has. She’s got an enormous media megaphone, a Twitter following, and how she shapes the meaning of her dream through the lens of fear, is what makes her so terrifying. It’s what makes him hate her. He finds himself daydreaming about her, wishing some sort of accident would befall her, not a fatal one, just one that would make it hard for her to broadcast the vitriol.

The room goes airless. He is full of revulsion. The smell of sweat, the smell of air freshener, the suggestion of those two competing odors, they waft from her dream gym into the analytic room, and he begins to feel nauseous. Imagining the smell, he starts to gag. He takes a deep breath, trying to right himself, another deep breath and again, and says to himself, It’s always the interpretation, not the dream itself, that counts.

The reminder brings him back to terra firma. He relaxes. A little. She proceeds.

“So, naturally, I’m thoroughly disgusted with myself. But what makes it kind of okay is that I realize that Diesel Chick has come to me in this way because she is warning me. Warning me about my own perverse stuff, yeah, I get that. The libtards hit you where you are just a teensy weak. That’s how their dream broadcasting operation works. But, see, Diesel Chick is also giving me a chance, like that chance in Gethsemane that I was talking about before you rudely interrupted me, yes, I noticed that, because Diesel Chick believes in me and believes that I can do something about this degradation. That this is my chance to help others even if the commandment has come in a she-wolf’s clothes. Or whatever.”

Now: the hateful plan itself. Triple distilled cruelty. There will be education camps for the confused, she says. You have to stay until you can answer all of the questions correctly. If that doesn’t work, anyone even thinking about doing what they do when they are in between things or whatever they call it will be deported. You will have to drop trousers at the Department of Motor Vehicles. You just will. Genetic testing before participating in girls’ sports. Electroconvulsive therapy is one option. Lobotomy as a last resort. Freeze that bank account up, mister, freeze it up. Unless you are a girl or a boy you don’t get medical treatment. You have to be tough that way. When dealing with genitalia you have to be as tough as Clint Eastwood.

He cringes. Clears his throat and throws her a lifeline to enlightenment.

“You know,” he says, “that Caitlyn Jenner just announced she’s going to run against Gavin Newsom in California, for Governor.”

He pauses, waits for a response. When nothing arrives, he presses, perhaps unwisely, perhaps too far.

“Trump is backing her.”

We were all so snuggly with ourselves, he thinks. We never thought something so ludicrous could ever happen. And then: look what happened.

He waits with her silence for a merciful stretch of time, letting her grapple with the cognitive pretzel. In the meantime, he too is involved in his own wrestling match, he knows, his mind grappling with its own half-tamed demons. It is unlikely that he will emerge from the struggle unscathed. Did he push her too far? Did he allow his disgust to overwhelm her? He is so tired of always being on def-con-high-red alert, constantly checking himself with her, watching himself even as he is talking, tracking his countertransference, measuring his words and gaming out their impact. He ties his tongue in a knot while urging hers to loosen.

His cheeks flush, the nausea returns, his fingers start to tap out some sort of morse code.

He is the one to break the silence. It isn’t completely intentional. He didn’t even realize that he was thinking of her, the famous case he read about as a psychiatric resident, as a cautionary tale, but just as the memory forms cogently in his mind, her name escapes his mouth with a rough, croaking breath.

“Dora.”

“Dora?” the patient asks. “From the chatroom? How in the world do you know about her?”

“Chatroom, no, no, not a chatroom…”

“Oh, my word, was she ever going on a wild tear the other day. I could not keep up with the train of thinking, her thought process, the connections she was making. But I was riding it, I was riding the wave of her brain. It was, well, it was like the best CrossFit set you ever had, blood pumping, muscles burning, brain expanding, lungs flooding your whole body with oxygen. It is like that, those Q groups online. Better than sex, sometimes.”

She pauses to consider the analogy.

He waits for the rest to rush forth, the verbal mudslide.

The patient opens her mouth, is about to speak, and then, yet again, she swerves away, avoiding recognition, seeking more distraction.

“Dora just put it all together for us that day,” she says, diving into her purse, pulling out her phone that is encased in sequined, MAGA swag. “I screen shotted it, just so that I could send it to you.”

Swipe, swipe, tap.

“There. I sent it to you.”

A little bell chimes inside his desk drawer. He turns about, opens it, warily, and takes out his own phone.

Sighing, he reads:

Now we are seeing what the New World Order is all about. They are dividing our Country to get to the end – a second wave of the pandemic – more Government Control and engineered chaos. We saw world peace – no wars – and a vibrant economy that benefited everyone. The New World order folks had to stop this and did it with a pandemic – shutting down the economy, controlling our movements, now microchipping the entire population with vaccine. And still they wear masks! Children should be liberated from libtard parents who force them to conceal their identity with a mask, all in the name of the Pandemic, easier when they go missing in the basements of pizza parlors. Brainwashing our children with black lives matter curriculum and getting us addicted and dependent on the drug of welfare. Our border is open not to invite children in (that is the ruse) we are open and an army of people who want to take our country down and to replace us. Yeah, you hear that right. They want replacements for white people, people more obedient to their regime. Criminals were let out of prison in every democratic state to join the Democratic Army BLM and Antifa. The current administration and people who committed acts of Treason will be arrested and tried by our Military who are sworn to protect the Constitution of the United States. It will not be pretty – stay safe – don’t get sucked in by the narrative of White Supremacist groups are out there doing the real damage.

He finishes. Looks up.

“Whaddaya think of that?” she asks, brightly.

He’s learned to let her word salad dress-and-toss itself, but he’s still reeling from his own previous, inadvertent revelation. Not that she caught it, but he did. Decades have passed since he first read the Dora case, about losing one’s analytic cool in the room, losing sight of the vested detachment. And he’s been there so many times before with this patient. No other patient has challenged him the way she has. He let it out, let it be known, in his weird, psycho-cryptology. It’s grandiose, he thinks, and yet, his identification with unexamined ambivalence is spot on. The name–Dora–means more than it seems. Still.

“That’s not the Dora I had in mind,” he says. “My Dora lived in Vienna in the late nineteenth century. She was a patient of Sigmund Freud’s. He had a hard time understanding her. The treatment did not go well, she quit, left him, and the analysis remained unresolved, fragmentary. It bothered him. He wrote a famous case study about her.”

“What does that girl have to do with me? Or with my dream? Or with my problem? I don’t mean to tell you how to do your job, mister, but I’m having a hard time seeing–”

The little boat in the harbor disappears around a crook of the shore.

“And where’s Vienna, by the way? It sure isn’t in my district, I can tell you that right now.”

He is still reeling. She was not the one with a verbal mudslide on the tip of her tongue. He was talking about himself, he realizes.

“Little Hans–” he blurts.

“Who?”

“No one. Never mind. Forget I said it. It slipped out.”

“Okay, pal, how do you know about Little Hans, too, just like you knew about Dora?”

“I don’t know about–”

“Little Hans runs the appliance stores out on Route 441. By the Kroger. He’s just a big teddy bear of a guy. Nice guy. Real sweetie. Lives alone. Donates lots of money to the campaign. And, yeah, some funky texts, too, sometimes, late at night, but, you know, boys will be boys.”

“That’s not who I was talking about.”

“Some really funky texts.”

“Little Hans–”

“But he’s just talking in the locker room. That’s all he’s doing.”

“Let’s forget all about–”

“I mean, what Little Hans talks about it pretty disgusting, actually, and I don’t think he would actually do that, but, you know, if he does, he’s a lone wolf head case and I still want his money before he goes off and the small business owner is the backbone of the heartland.”

“We’re not talking about the same person.”

“I guess I shouldn’t talk like that about Little Hans since I’ve turned out to be such an unforgivable pervert myself.”

In his mind, he unloads. It all pours forth. All of it. The clinical term–decompensation–does no justice to what he imagines. Mentally, he rages: it is no excuse that she didn’t do well in college. That she can “get it” just fine if she wants to, but she has jammed her own fingers into her ears and has blamed everyone else for the fact that she can’t hear very much. She doesn’t know from working class. He was the real working class one. Worked with his own two hands. Hammers. The adze. The nail. She is not afraid because of a dream about Diesel Chick. She is afraid of chaos, of ambiguity. That’s the real problem. And in the face of complexity–at least as she perceives it–she shuts down, she freezes, she becomes phobic.

He lets it rip, inside.

He has lost track of the silence or the last thing he’s said.

It’s one hell of an internal monologue.

He imagines whispering harshly, through gritted teeth, explaining to her how he understands perfectly well about how her death-to-everyone-and-everything-I-don’t-like zapping machine works. She can’t stop putting everyone and everything into categories. This or that. All good or all bad. You are with me or against me. You make yourself into a botox-seeking Barbie with gravity defying shoes or you’re not really much of a person at all. Look at Leni Reifentahl, for example. This is exactly Leni Reifenstahl swill, with all of her perfect, sacred, Aryan bodies flying like objects through the air. Defining the bodies of others according to one’s dream definition of one’s own body is fascism. That’s what she’s messing around with here. Fascism. Sorry about your kid, but, you know, the eugenics squad came around and they just did what they had to do and followed orders.

Dr. Pop was right. All along.

Doesn’t she see that all of this awful stuff can lead to?

“Which reminds me,” she chirps.

He slumps.

“There’s something I’ve been meaning to ask you.”

No words can brace him sufficiently.

“I’ve heard different opinions,” she says, narrowing her eyes at him.

Can’t she just leave? As in forever?

“Okay. I’m just gonna ask,” she says, crossing her arms.

And yet if he cuts her loose in this state, isn’t that kind of a crime against humanity?

“Are you really a Christian?” she asks.

He raises an eyebrow.

“How could I not be? I am, after all–”

“Or are you a Jew?”

At first, he doth in silence fume. And then: an opportunity, a very rare one, verily he glimpses.

“Because I just don’t see how you can possibly be a Jew.”

He clears his throat.

“I’m both,” he says.

The patient falls silent.

The patient starts to tremble.

“At the same time.”

The patient screams.

“Impossible!” she cries.

“It’s true. How else can you explain it?

“I don’t believe what I am hearing!”

He leans forward. Makes eye contact at last.

“Are you questioning me, Marjorie?”

He has seen some very strange things in his time. But this is full strength, John of Patmos stuff. Epic, schizo show. He has never actually witnessed an exorcism. The patient’s neck snaps back, and in the voice of Richard Nixon she announces that he is not a crook. The patient lurches forward. In the voice of Charles Lindbergh, he announces that America should come first. A thousand little black bats fly out from her ears, filling the room, each with a human face. He identifies a few as they whirl by. Phyllis Schafly. Joe McCarthy. George Wallace. From her nostrils pour trails of small, translucent scorpions, also with human faces. There goes Joe Arpaio. Tucker Carlson. Mel Gibson. Lee Greenwood. Tiny red ants crawl from her pupils. Ted Nugent, Rudolf Giuliani, Jeanine Pirro, that woman who testified in front of state legislatures about the voter fraud she witnessed, and that man, that general, who shouted out to a crowd, lock her up, lock her up, lock her up….

The scorpions and ants sprout wings and dance with the bats. The shuddering, opening bars of “Thus Spake Zarathustra” blasts from an invisible stereo system. A Salvation Army marching bands plays backwards. Cannon fire from upon a distant hillside. Peals of thunder and of bells.

Then it’s over. The patient lies slumped in the chair.

“Where am I?”

He talks her through it, slowly, gently. About her phobia. About her dream. About her plans.

“Why would I want to put people in camps?” she asks. “That’s just terrible.”

“You tell me.”

“I mean, what have they ever done to me?”

“Good question.”

“Why have I been so hung up and so nosy about other people’s business?”

“Sometimes, the ‘why’ from the past doesn’t always matter. Sometimes the point is moving forward.”

“On that front, I super need to reverse course in front of the whole world and retract all sorts of goofy things.”

“And then?”

“Pack up the office and go home. And stay there. I really have no business doing any of this. And, yeah, they’ll have to have a special election, or something but, really, can they elect anyone any worse than I’ve been? I mean, c’mon. As is, I’m a loose cannon.”

“Interesting insight.”

“Boy, oh boy, do I have some fences to mend.”

The patient looks at the ceiling.

“And another thing.”

She scoots forward, leans toward him, lowers her head, clasps her hands. She speaks quietly, conspiratorially.

“I’ve just been dying to tell someone what a terrible fuck that Marc Rubio is.”

She moves forward again, to the chair’s very edge.

“And I don’t mean ‘fuck’ like he’s a stupid or gross or mean guy, or whatever, even though he is. I mean ‘fuck’ like, you know, like fucking, like intercourse. It was awful. And I mean was. Just this once, mister. Just this once.”

“Interesting,” the doctor says. “But he’s in the past now. Let’s keep looking ahead, though, as I said. Shall we?”

“Sounds great.”

“For example–”

“Yes?”

“About billing. About your tab. You’ve rung up a doozy here.”