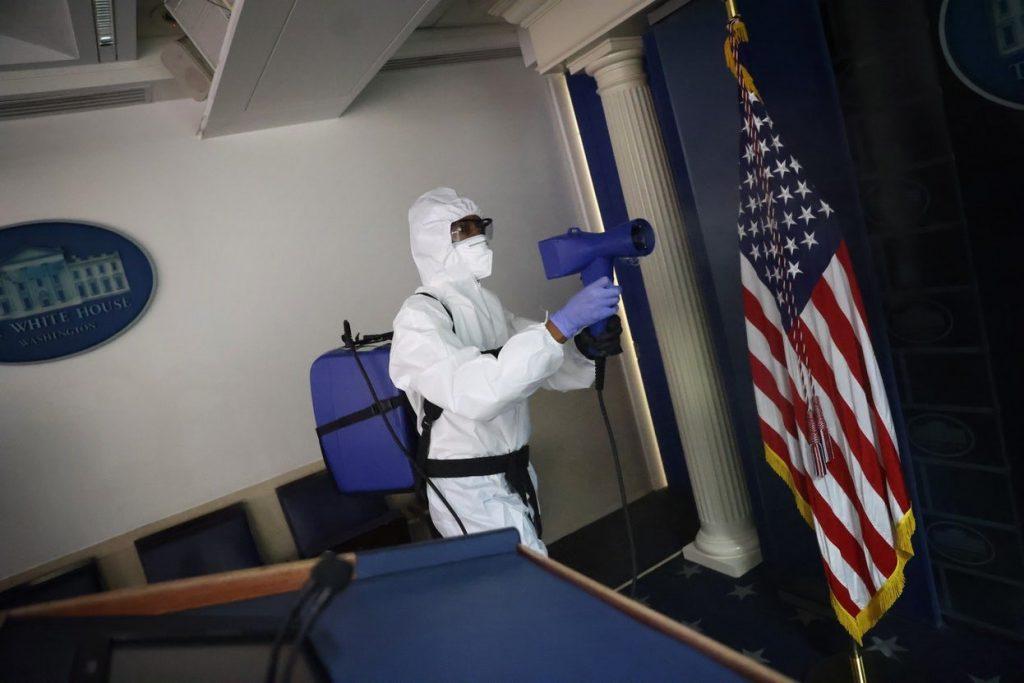

The White House Press Briefing Room is dark again. The last time the lights went off, Sarah Sanders had grown tired of skirmishing with the press, and the Commander-in-Chief had come to believe that he was his own best listen-as-I-walk-to-the-helicopter megaphone. Now an entirely foreseeable COVID-19 outbreak among the President’s inner circle has infected numerous individuals at the White House, including Kayleigh McEnany, the Press Secretary, and several members of her staff. Undeterred, carrying on from quarantine, McEnany has continued to provide candygram propaganda pushing Christian nationalism on Fox News, via remote video feed. She typically stands in front of a nondescript bookshelf, one featuring a square clock, the hands of which appear to have stopped, and a small, white, ceramic elephant. She looks sincere. She remains upbeat. Meanwhile, in the Press Briefing Room, her old arena, a solitary figure in a hazmat suit sprays disinfectant, asking no questions, giving no answers, telling no lies.

Given her age, sex, and apparent health, the odds are that McEnany will be able to return to her post, if it indeed still exists for much longer. It is reasonable to wonder, as many have: might an encounter with death, even at arm’s length, alter one’s perspective on an illness that one has lied about for so long to so many? A sign of humility, perhaps? A glimmer of empathy? For his part, during his maskless, rambling televised speech from the White House balcony, Donald Trump was eager to demonstrate that this psychology is so rigid and deformed that any such insight, much less subsequent change, will not be forthcoming.

When the lights come on again, assuming they do come on again, sometime during the remaining days of this administration, McEnany will, for admittedly very different reasons, remain similarly unaltered by her experience. Regardless of the pandemic, her mission, as she sees it, will remain unchanged. To that end, unlike every one of her predecessors in the role of Press Secretary, she will continue to refuse to engage in anything that resembles a give-and-take conversation that attempts to persuade. Instead, she will return, as before, and preach.

So she must. McEnany has, after all, given every indication that she is an unwavering theocrat for whom democratic principles are meaningful only to the extent that these principles aid in the establishment of a law more righteous than any wrought by human hands. Indeed, should she return, she may, on the rebound from illness, conduct her briefings with heightened degrees of enthusiasm and conviction. The universe is controlled by the Divine, she knows, and she may feel compelled to tell a holy story. Although almost martyred, she was lifted from among the almost dead by the inscrutable wondrousness of grace. Unlike, presumably, those who were not so lucky to be similarly selected. She won’t say it exactly that way, of course. Christian nationalism can’t sound so blunt. She will emphasize how thankful she is. Sainthood is not only rewarded to holy fools, after all.

McEnany’s identification–sort of, at a remove, second hand–with martyrdom goes way back. She has written that, as a child, her hero was Rachel Joy Scott, a 17 year old who was murdered at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, by Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. Scott was allegedly targeted by the two because of her outspoken, Christian beliefs. A peculiarly passionate, apocalyptic fixation on McEnany’s part, one notes, for someone who was only 11 years old at the time of that mass shooting. The slain child’s significance did not dim with time. McEnany also dedicated her 2018 book, The New American Revolution: The Making of a Populist Movement, to the memory of Rachel Scott. The book does not argue for a narrow interpretation of the 2nd Amendment.

In the present administration, McEnany, we know, is in good, similarly besieged, company that is proud of its vocal Christian nationalism. Vice President Mike Pence has stated that “some of the loudest voices for tolerance have little regard for Christian traditional beliefs.” Attorney General William Barr has declared that “modern secularists” are not only intent upon destroying “the traditional Judeo-Christian moral system,” but they are succeeding in doing so, assisted by “their allies among progressives who have marshalled all the force of mass communications, popular culture, the entertainment industry and academia”. Although they are not members of the administration in the strict senses of these words, Supreme Court Justices Thomas and Alito recently asserted that the court’s 2015 decision Obergefell v. Hodges–the case that guarantees the right of same-sex couples to marry–“enables courts and governments to brand religious adherents who believe that marriage is between one man and one woman as bigots, making their religious liberty concerns that much easier to dismiss.”

So the battle must be joined. McEnany has done her part by helping to transform the previously secular tradition of the White House press briefing into a sacred one. She has also provided a glimpse of the forces she believes she is personally up against. On May 22, 2020, the discussion in the Press Briefing Room concerned methods for slowing the spread of Covid-19–methods that the administration, in retrospect, would have been wise to study and to implement. Governors in several states had recently banned large indoor gatherings, including those held at churches, mosques, and synagogues. McEnany stated that the President had “ordered” these governors to reverse this decision and to allow the gatherings to occur. Reporters pressed McEnany, asking her to cite the President’s legal authority to do so. Exasperated, she did not answer the question, as if civil, legal authority itself was inconsequential, but she did observe: “Boy, it’s interesting to be in a room that desperately wants to see these churches and houses of worship stay closed.”

Really? Who, in the real world, is actively, desperately trying to slam the doors of these houses forever shut? Who has taken on such a doomed, absurd crusade? Is she talking about atheists? While damned, atheists wouldn’t seem to pose much of an actionable threat, given that there aren’t really that very many of them and that they don’t really seem to care what happens in churches one way or another, opened, closed, or otherwise.

But such pedestrian questions of fact miss the larger, mythopoetic point. These reporters are not the earnest, civic-minded folks they might at first appear to be. They are, she more than subtly suggest, soldiers being played, perhaps unwittingly, perhaps even against their own will, by the grandmaster who has wanted to destroy all that is good since his own fall from heaven before the beginning of time.

On a flatly strategic level, McEnany’s rhetorical style–she affirms rather than argues, she repeats rather than responds–dovetails nicely with Trump’s misbegotten, double-down-on-the-double-down calculation that his victory depends upon solidifying an already rock solid base and riling up any under-a-rock white nationalists who somehow failed to get sufficiently hostile in 2016. McEnany herself surely nurtures a few earthly, very much of-this-world, motivations for doing what she does. Aside from idealistic Christian nationalism, there is, after all, money–a lot of money–to be made here and McEnany has, if nothing else, secured a lifetime gig on the fear and privilege circuit. In fact, if Trump loses, as it now appears likely, and America tailspins into anarch-o, sociolist-o, secular-o chaos as warned, her term on the go-to panel of right wing talking heads may be all the more assured and lucrative, given that she can testify as to how the horrors she prophesied have indeed come to pass.

God fearing, on its own, is a very old time-y money-maker. But too great an emphasis upon McEnany as mercenary can obscure the long standing, considerable power of her faith based rhetoric. Her practice of Press Secretary-as-preacher draws upon distinct, Protestant theological traditions and practices that have proven to have great and sometimes intense psychological appeal and influence. Their popular effect is hardly limited to those who identify as Protestant. The People of Praise, the small, insular religious group to which Judge Amy Coney Barrett belongs, began in Pittsburgh, in 1967, when Catholic academics at Duquesne University experienced a series of direct, ecstatic encounters with what they believed to be the Holy Spirit. While the history of the Catholic Church of course includes any number of ecstatic visionaries, the validity of these visions–their official certification–has always been at the discretion of Church authorities. The People of Praise has not sought, nor received, such validation. Nor is it likely that they should or will, given that speaking in tongues is hardly a common, acceptable Catholic practice.

All of which is strikingly similar to the experience of Martin Luther, of Wittenberg, Germany, long ago, in the 16th century.

The oft-told and heavily sanitized tale goes like this. Luther was a very unhappy Catholic priest. While not prone to visions himself–he was a bookish and studious man–he was enraged by what he saw as rampant material and spiritual corruption within the Church. He was repulsed by the fact that his fellow priests assured people that they could buy their way into heaven through the purchase of “indulgences.” He was also maddened that the Church virtually ignored the teachings found in the Bible, instead preferring its own, self-invented arcana. The Bible, after all, was the revealed word of God. As brilliant as he may have been, Saint Augustine’s confessionary ruminations, for example, could hardly be thought to be more important than the actual words of Jesus Christ, as directly recorded in the New Testament.

Open the book. Read it yourself. You will find no rosary beads, no confession box, no discussion of venal and mortal sin, no realm of Purgatory. These, to Luther, were needless elaborations and ornamentations. Why elaborate and ornament, why cloud–and in Latin, a language incomprehensible to the flock–what was already perfection itself?

He attended, in particular, to Acts 16:31. “And they said, Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved, and thy house.” It was a simple enough sentence. It also offered a devastatingly simple remedy to human agony. All you had to do was believe. Believe and you will be saved. Believe and you will live forever. What was so hard to understand about that message, written, as it was, for your instruction? This is God’s universe, after all, and if He wants to make salvation simple, isn’t that His prerogative?

And the social revolution that this keen insight implied, as Luther saw it, was only the beginning. A psychological one–he would probably have used the word “spiritual”–was at hand as well. If belief was the whole of salvation, that meant that you didn’t have to actually do anything in order to be saved. No strenuous pilgrimages were required. No good works needed to be undertaken. No mea culpas necessary. You didn’t have to turn to priests, or rabbis, or imams for help: you could save yourself, right here, right now, wherever, whoever, you are. The whole transaction, the whole once-demanding task of redemption, can occur, almost instantaneously, inside your head.

Anyone, therefore, almost entirely without guidance, was instantly capable of hearing and understanding unaltered words previously known only to beatified mystics. Luther’s conclusion was revolutionary and, so it would seem, intensely democratic. Certainly, Americans have become particularly adept at connecting these two ideas. They are not, however, the same, as Luther would have been the first to warn. Some of God’s communications, he maintained, were more meaningful than others. His own ruminations, for example, were significant. The ravings of the village idiot, wandering through fields calling himself Angel Gabriel, were not. Witches, who could steal your milk just by thinking about a cow, he believed, might need to be burned at the stake now and then. His contemporary Jewish visionaries composing the Kabbalah? Their “houses should be razed and destroyed” and “all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, in which such idolatry, lies, cursing, and blasphemy are taught, be taken from them.”

In time, the brutal aspects of Luther’s seemingly inclusive, seemingly participatory, seemingly individualized, seemingly democratic, theology withered and fell from the story. The vast majority of Protestants who now gather and worship in America, having been made democratic more by history and culture than by Luther, would obviously find his intolerance repulsive. Un-American, in fact. It is not the entirety of Luther’s message, however, that remains so deeply and widely influential. What remains is the appeal of his means by which messages may be read, may be discerned. They can be done so through a radical simplicity. How does one decide what is true and what is false in an age of disinformation, for example? The seductive appeal of Luther’s theology–itself much simplified–provides an answer. What is true is what you believe.

“‘Tis a gift to be simple. ‘Tis a gift to be free.”

So goes the ecstatic Shaker hymn.

He will go on trying to break apart that devotional rock in your head with all sorts of lures and traps. He will come in the guise of the debater, the equivocator, the endless elaborator. He will, through the mouth of a reporter, insist that “it’s not so simple as that.” Speaking through the mouth of another reporter, he will try to start an argument by ticking off examples of your many logical inconsistencies. Do not engage in the “proof” game. There may never be any “proof.” This is not about “proof.” This is about belief. This is about the instantaneous miracle of faith. Frustrated by your strength, he will appear to relent, slightly, invitingly, and will offer a compromise, a middle ground, a “safe space” where one can “agree to disagree.” But how does one compromise with the agent of Armageddon? To enter into conversation, much less an understanding with him, is to enter No Man’s Land unarmed. Do not shake his hand. It is not a hand, after all.

The lights come back on in the White House Press Briefing Room. As we know, it is not just a room. It is a metaphoric space, spiritually configured for a performative act of Christian nationalism. It has visible and invisible qualities. It is a beach in Normandy-Upon-the-Holy-Land, one that she, a foot soldier, must storm and take back from elite mainstream media priests. Rather than an M1 Garand rifle, she is armed with tabbed binders. No camo: rather, a jewel-toned dress. Many on that real D-Day, along with their dog tags, wore a cross at the neck. She does too. Many, on that real D-Day, involuntarily pissed or vomited or shat in abject, animal terror amid mortar and machine gun fire. She, however, in faux combat, will project a serene Sunday school teacher vibe with breezy good manners, occasional frowns and disappointed finger wags as she engages in a game of words: a game that is only rarely and only very reluctantly played on any actual battlefield in this world.