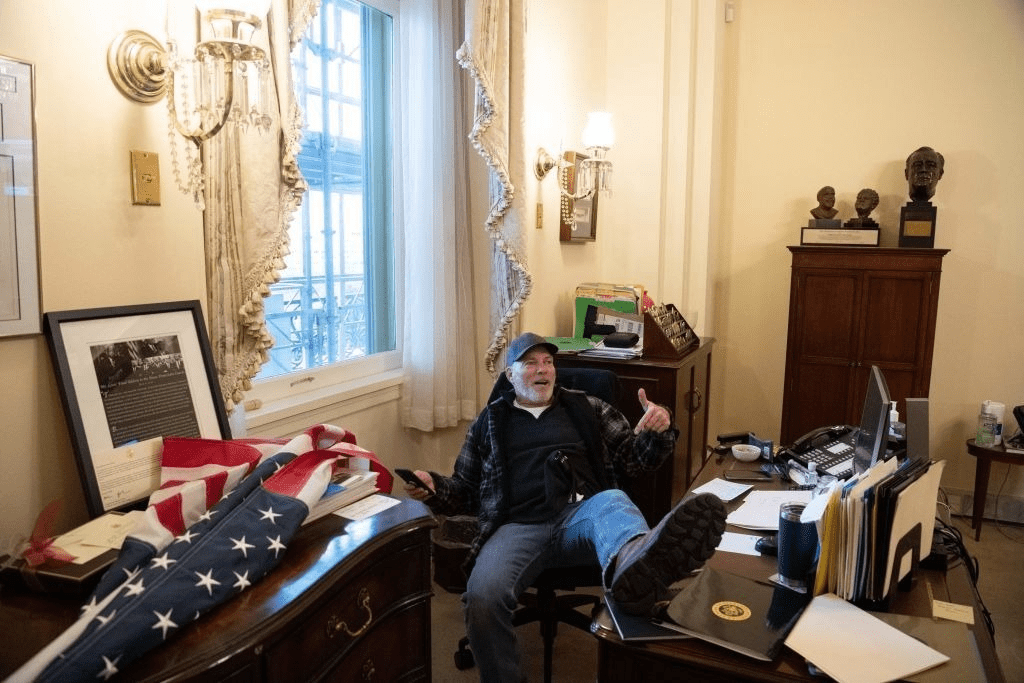

Our first glimpses seemed carnivalesque, disorganized, spontaneous, a MAGA circus of sorts. A painted clown with satyr horns, howling not at the moon but an empty Senate chamber. The mute extras from Trump rallies, guileless, taking selfies with statues and each other, the dead and the living, leaving their digital footprints and corporal fingerprints everywhere. Each day strips away these first frivolous looks of the dystopic flashmob, the last hurrah, one can hope, of the Trump era. Yet by the minute, these images are giving way to truths more menacing and orchestrated and violent.

The insurrection of January 6 left an abundant visual record. A powerful collection of images by brave photojournalists. The copious archive of surveillance video, inside and out, from every angle and passageway of the Capitol Building. The more official, procedural feeds of HouseTV. The social media production of the insurrectionists themselves who, giddy with transgression, posted and boasted and tweeted.

What we do not yet have is a complete sense-making narrative of the event. In the absence of context and explanation and omniscient voice-over, our storytellers lean on splitscreens.

Left: The United States Capitol, January 6, 2021. Photo: Mike Theiler Reuters.

Right: Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, Georgia. January 6, 2021. Photo: Doug Mills, New York Times.

A lot has already been said about the photo on the left, of the Confederate flag flying for the first time in the Capitol. In 1861, eleven states across the South seceded from the United States and became the Confederate States of America. Four of them–Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, and South Carolina–published declarations of secession and claimed, without a shred of ambiguity, “our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery.” Each of the confederate states, in only superficially different ways, named slavery as the underlying social and economic reason for leaving the United States, the white supremacist glue that held their bond together through the Civil War. The Confederate flag itself gained traction as a symbol only much later, after the Civil War, after the confederate states rejoined the union, even after Reconstruction,. A symbol born in belatedness and nostalgia, inseparable from legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, and the KKK, the Confederate flag had never found its way into the Capitol until January 6.

The astonishment produced by the photo on the left has largely eclipsed the historical significance of the photo on the right. Taken together, the two traffic in strange historical ironies, each one relaying messages about our immediate future and reverberating past: The two men on the right, a black pastor and Jewish filmmaker, will join the Senate in the coming days, just in time to render judgement on the image on the left, which displays the very banner of exclusion and oppression of those two men.

Left: Black Lives Matter protesters, taking a knee before the local police in San Jose, California. Photo: Dai Saguro, San Jose Mercury News, summer 2020.

Right: ProTrump Insurgents, overtaking police barricades at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. John Minchillo, AP.

We go splitscreen when more than one story demands our attention. Or when two stories, unfolding in parallel, collide and represent such contrary points of view that they reveal a deeper truth. One of the first storylines to crystallize about January 6 has to do with racist patterns of police conduct, the different experiences of white citizens and black and brown citizens. Compare-and-contrast splitscreens of these racist patterns surfaced and circulated through news and social media. On the left, an image from the summer of 2020, when Black Lives Matter protestors of color embody exaggerated gestures of performative deference to police, who nevertheless approach them with automatic rifles. On the right, Trumpian insurrectionists openly threaten police, taunting and chasing them, sometimes taking selfies with them, easily overtaking their metal barriers and using them as battering rams to break into the Capitol Building or as ladders to scale the walls of the edifice. In spite of intelligence warning of warlike and violent action, Capitol Police were dramatically underprepared for the day. Early investigations indicate that the insurrectionists themselves included members of police departments and military. Many have speculated that had this insurrectionary mob been made up of people of color, and not white supremacists, we would still be counting the black and brown dead.

Left: Trump speaks to his supporters, inciting them “to fight like hell,” at the Capitol, where they staged a failed coup. Photo: John Minchillo, AP.

Right: An insurgent breaks into Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s office. Photo: Saul Loeb, Getty Images.

Over decades of common rhetorical usage, the splitscreen is a staple trope of broadcast and cable news. If anything, its rhetorical force has multiplied in the age of digital feeds, high speed networks, and cable television. When shown a splitscreen, we create linkages between what we see on the left and what we see on the right, guided by our narrators, who toggle back and forth between them in their narration. Emphasis on one now, then the other, and back again. The rhetorical relation is not limited to any single idea. It can express the passage of time: before and after. Or spatial orientation: on the left, the front of the Capitol complex, on the right, the building’s side entrances. Or figure/ground relationships, giving wide context in establishing shots and close-ups of critical agents of action within that place. Splitscreens can imitate and thus draw upon widely digested film language, like reaction shots: on the left, we see the President speaking, on the right, we see his rapt audience, growing more animated.

Left: The doors to the house chamber are broken. Photo: Erin Schaff, New York Times.

Right: Members of Congress are rushed to secure locations, as the insurrection reaches the door to the chamber. Scott Applewhite, AP

On January 6, 2021, insurrectionists wrote the words “Murder the Media” on the walls of the Capitol. As photojournalists suffered bodily attacks from the rioters and insurrectionists, their equipment was also stolen and destroyed and, in some cases, turned into instruments of battery. The photographs that were taken that day at the Capitol formed our first impressions of the insurrection, and as our understanding of that day deepens and grows more complex, those images now take on new meaning. It is critical to understand how we make meaning with photographs, how they are enlisted in rhetorical gestures like the splitscreen, how our verbal narratives anchor them to timelines and storylines. But it is just as important to try to understand, if we can, the circumstances that quite materially frame them, the conditions that quite literally give rise to them.

The photojournalist Julio Cortez posted this video to his Instagram feed shortly after the Capitol building was secured. His photograph–of the translucent, upside down burning American flag–became emblematic of the long summer of 2020, taken in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in police custody. The Battle Hymn often displays that image in the banner space of our blogs. On January 6, the photojournalist John Minchillo, Julio Cortez’ colleague from the Associated Press, was taunted and threatened and attacked by the Trumpian mob. Minchillo’s photos, of the MAGA rally and insurrection, are featured above in the body of the blog and in the banner image. Cortez tracked the attack of his colleague and captured the event with a GoPro video camera, likely affixed to his body: a new language of documentary witness for the age of insurrectionary style.