Language is perpetually in flux: it is a living stream, shifting, changing, receiving new strength from a thousand tributaries, losing old forms in the backwaters of time.

E. B. White, The Elements of Style

The backwaters of time, now and again, insist upon an audience, as they cry out, I am viable, I am relevant.

Rising, desperate, refusing to settle quietly in the still backwater, where they would otherwise languish, in more conventional times, and become quiet and quieter. Instead, they struggle against the strong currents of history, paddling and splashing with the fury of survival, trying to find their way back to the main of the stream, where the water is cool and clear and flows with plenty of jumping fish. In spite of the wild commotion and the gulping for air and the turgidity their brash movements create, they nevertheless manage to evoke the warm, flattering light of nostalgia, a rhetorical operation that, once upon a time, worked like a southern charm.

The message arrives in an old-fashioned way, through the horse-and-buggy mail, in an envelope swollen with extravagance and calligraphy. The invitation goes out to a select band of possible attendees, who must thumb through all of the tasteful, color-coordinated little pieces of paper in the assemblage, eventually to find the essential R.S.V.P. card, which is paper-clipped to a second, much smaller envelope. This tiny paper vessel is pre-addressed and pre-stamped, to ease the effort of returning the already phrased reply to its sender, and hence to close the circuitry of the message. The only manual labor required: check the appropriate box. The senders of the message keep a running tally as the missives return home to roost, so that everyone will know who on the guest list is whom and thus all in for the celebration, or revival, or cross burning, or worse.

Just such a missive arrived on Georgia Governor Brian Kemp’s desk the night of March 25, 2021.

The message came from the Georgia State Legislature, with the unassuming name SB 202.

Photographs of Governor Kemp’s authorizing signature seem studiously composed, a near painterly tableau. The governor is flanked, in careful symmetry, by three-and-three white men, uniformly attired; their reflections in the shiny surface of the conference table seem to double their number. Over their shoulders and above their heads hangs the silent centerpiece of the scene, a mute witness lending its approval to the proceedings and setting the tone and context and supplying the clues to crack the not-so-hidden code of the bill’s intent.

A lost form calling from the backwaters of time. It is a painting of the Callaway Plantation.

According to the census of 1860, the plantation was one of the larger houses of slavery in Wilkes County, Georgia. The Callaway family, English immigrants who made their way to Georgia from Virginia and then North Carolina, grew cotton for export and owned several hundred slaves. The family still owns significant acreage around the plantation, though the main buildings and grounds are now an open-air museum, an attraction of sorts for tourists.

In the painting, the road to the manor is flooded with unrepentant sunlight. Widening and welcoming, the road opens onto the bottom edge of the canvas and abuts the frame. In the room where it is displayed, the painting itself is flanked by the authorizing posture of two American flags, from the democratic present and the colonial past. All of these formal arrangements–the symmetry of men, the flag, the inviting path–offer up a tempting invitation to jump the border of the painting’s frame and time-travel down that fragrant antebellum road.

Much has been said about the content of Georgia’s SB 202, and now of Florida’s SB 90, and of Texas’s SB 7, and similar forthcoming bills in Arizona and Michigan and Ohio, all metastases of the same antidemocratic cancer spreading across state lines, everywhere a Republican legislature maintains the lie of a stolen 2020 election, which, in turn, justifies a zealous crusade against an entirely imagined, wholly fictitious fraud.

It bears remembering what these laws collectively do. Their aim is to restrict access to ballots by limiting early voting, making mail-in ballots more difficult to obtain and changing the rules about how to request them or even who qualifies for one. Ballot drop-off boxes will be fewer in number, accessible for shorter windows of time, and for only certain hours of the day, and only on early voting days. Early in-person voting hours and days will also be limited, and many polling places, especially in cities, will be eliminated as well, all specifically engineered to produce longer lines to vote in person, which in the hot Georgia or Florida or Texas sun, could result in greater fatigue for older voters or voters in poor health or those with disabilities and for people who have to work; all of which discourages voters from turning out in the first place. It will be illegal to offer water and food to those waiting in those longer lines, even to the elderly, who might wait for hours to vote, and those with health concerns, whose stamina may be compromised.

The restrictions will, of course, also target the working poor and African American voters and urban voters, whose polling places will be more crowded and disproportionately burdened by these restrictions. The Texas law sheds any coyness when it calls for “purity at the ballot box,” a direct citation of its own racist state constitutional charters and legacies in Jim Crow, voter intimidation, and whites only primaries. The cherished African-American tradition of “souls to the polls”–the ritual of voting on Sundays after church–is an explicit target of Georgia’s SB 202, which curtails early voting on Sundays, and of Texas’ law, which eliminates Sunday morning voting entirely. Urban polling places will be combined with other precincts, or long familiar polling places may be changed; meanwhile adherence to precinct-only voting will be strictly observed and enforced, so that a voter cannot submit a vote in an adjacent or formerly assigned precinct. The Florida and Texas laws will give more power and authority to partisan poll watchers to monitor the proceedings and to report irregularities, powerful responsibilities in the hands of everyday Floridians and Texans, who are likely untrained in the legacy of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and who may be chosen for the occasion on account of their hostility to it.

The Georgia bill passed through the State House in the morning, the State Senate in the afternoon, and landed on the Governor’s desk for signature in the evening. A single day saw this retrogressive law through the channels of power. Little time for revision, no time for debate. The Georgia law would remove the Secretary of State from the board of elections and allow members of the legislature themselves to determine the outcome of their own election campaigns, potentially in contradistinction to the will of the popular vote. Likewise, the Texas law, under the cover of night, at the last minute, with no debate, added a provision that would allow a judge to overturn the results of an election, and defy the will of the people, if he or she were presented with prospect of alleged fraud, even if it were an invention of those who clearly lost.

Just outside Kemp’s highly curated tableau, as his pen supplied the proverbial stroke, State Representative Park Cannon, who did not receive an invitation to the ceremonies, wanted to look on as a witness, to take her place at the table beneath the Callaway Plantation. She had voted against the bill that morning and knocked on the door of Kemp’s office that evening. When her query received no response, she kept knocking.

Representative Cannon may have been surprised by the force of her exclusion, but it is just as likely she knew exactly why she would be refused. Her presence would disrupt the symmetry, homogeneity, and homosociality of the tableau, and would introduce differences of many kinds. Of race and gender, of political representation and perspective, and of lived experience. Her presence would change the context and the meaning of the message and expose the codes of racism that everywhere underwrite the intent of the bill. She would signify a contrary message, one heterodox to those securely ensconced there in the inner chambers of Kemp. She would call uncomfortable attention to the stagnant waters from whence SB 202 had come, and reveal how the backwaters of time rushed forth to exclude her, with actual force, in the form of rough bodily treatment, as the arm brace she wore in the following days would indicate.

The violence of her exclusion measures the real and imagined power of her possible witness. Otherwise, why would the desire to be present and to bear witness to a signature be understood as a criminal act and thus provoke such a punitive reaction? As a witness of the scene, Cannon herself is a complex intersectional nexus of representation. She is an elected representative, a political proxy for her constituents; according to our system of representative democracy, she represents those who live in her district, which spans two urban counties of Atlanta. The voters who elected her are those whose political representation is most threatened by SB202, urban and black voters, and asian-american voters, and progressive and liberal and democratic voters, those who will wait in long lines, during shortened poll hours, with curtailed access to voting by mail, and quite possibly surveilled by hostile partisan poll watchers looking for any imagined infraction that might invalidate their ballot.

Cannon must have understood that, in this moment, she embodied the historical struggle that illuminates the meaning of the Georgia law. In it, we sadly glean what will remain of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and of Cannon’s generational inheritance from the late John Lewis, her fellow Georgian and certain mentor, and thus to the Civil Rights movement broadly, and to the terrible toll of the Jim Crow era, which threatens to rise again, precisely through SB202 and its mutations. It is difficult to imagine two more contrary movements of history unfolding so vividly in one scene, on either side of a guarded door, side-by-side and simultaneously, a space so concise in its presentation of antagonisms, a theatrical play of history. On one side: a signature, an authorizing act. On the other: a knock, a request to see and to be seen, the dynamic question of witnessing. This particular signature, an attempt to reduce and to contain and to limit. The knock, a refusal to be silent and a demand to be present. In the interior sanctioned space, the restriction of undesirable political representation. The exterior, excluded space: a vivid illustration of dynamic, expansive political representation. At work at the level of democratic representation and therefore of the inclusion or exclusion of voice: an expansive field of participation or a restrictive band of privilege.

After her release from jail, Cannon tweeted:

“I am not the first Georgian to be arrested for fighting voter suppression. I’d love to say I’m the last, but we know that isn’t true. … But someday soon that last person will step out of jail for the last time and breathe a first breath knowing that no one will be jailed again for fighting for the right to vote.”

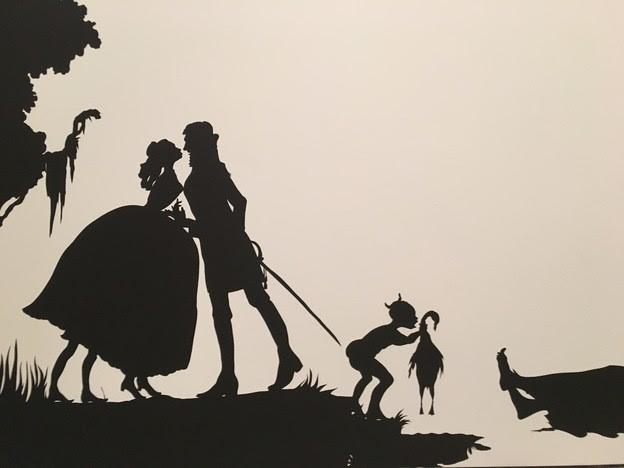

The power of situated observation is the essence of witnessing. Embedded in time and place, the setting of context, history and geography are the grounding dimension of witness. Akin to context, the more elusive notion of code, how one perceives what one sees, how one understands the world, is animated by often implicit ideas. A conflict of signs and codes bears down upon the signature of Georgia’s SB202 into law. The code governing the semiosis inside Kemp’s office is given away by the painting of the Callaway plantation: the romance of the Confederacy and the persistence of white supremacy, “Tara’s Theme” from Gone With the Wind. Cannon’s knocking–the sign in dialogical counterpose to Kemp’s signature–is animated by the codes of the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s, and the signature of two key pieces of legislation under threat today–the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The denial of Cannon’s witness in 2021 evinces its powerful presence in 1964 and 1965, when the invitation to Lyndon B. Johnson’s ceremonial signature was specifically addressed to Martin Luther King, Jr., whose gaze upon the act, in that moment, authorized it and gave it meaning. King’s gaze represented a period at the end of an era’s sentence, of petitioning Johnson, and of marches, and subjection to police violence, and the perennial denial of voting rights.

Roman Jakobson’s structural account of communication, noted above, allows us to see the semiotic conditions that give dimensional meaning to any act of communication–verbal, gestural, musical, visual, literary. It illustrates a dynamic exchange between messengers, who both send and receive missives, shape them and interpret them and reconfigure them. The act of witnessing summons up all of these elements and avows them and commits them to acts of public memory.

Jakobson himself tracked a very particular pathway to the United States. He was born of Jewish parents in pre-Soviet Russia and came of age as a young linguist shortly after the Bolshevik Revolution, which had sparked a brilliant decade of formalist experimentation in language and visual art, design and cinema. Enthralled with the expansive conception of language and its capacity, at that moment everywhere evident in the young USSR, Jakobson charted a course in the study of communication. As Stalinist orthodoxy abruptly ended the decade of Russian Formalist invention, Jakobson became a target of totalitarian censorship. He fled Moscow and found a number of short-lived homes across Europe. A stay in Prague, where he left a lasting linguistic mark. Berlin and Copenhagen, as Europe became more turbulent. Finally, Norway and Sweden, scarcely staying a step ahead of the Nazis, before he escaped Europe altogether, stowed away on a cargo ship, with the philosopher Ernst Cassirer, to New York City. Jakobson eventually taught at the New School for Social Research, where he may or may not have crossed paths with Hannah Arendt.

Writing in isolation from a cell in a Birmingham, Alabama jail, Martin Luther King wrote, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” Opening these channels of mutuality and inviting everyone in, as observers and witnesses of history, as we make it and as it is being made: the transmit of a message, a web of interconnection, from inception to reception. Written in the active voice and received in a reciprocal frame of engagement, from observation to narration.