God knows, I’ve tried. Somehow, surely, the words “cheeto” and “baby man” and “spray tan” could be spun into some sort of twinkling yet trenchant comic confection. You have a master’s degree in fine arts, I heard a demon say. And if this haircut isn’t an easy target, it may be time to hang it up. Now, after churning out several chapters of mockery, and some YouTube demonstrations of wise guy cheap shots, and even a few posts consisting of pretend-erudite ekphrases, I, years after embarking upon this personal and communal quest to pin the appropriate words to the appropriate ass, must now admit defeat. Not even did I land a pie successfully on one of the movement’s leaders’ enormous, omnipresent puss.

Not really.

I always had an excuse, an ever ready escape hatch, waiting nearby, in case of emergency, and although this particular alibi has the dulling drawback of pure obviousness, it’s no less true for being so obvious. Trump was, and is, a monster who did, and does, monstrous things to innocent people. If I can’t do funny with this guy, fine. His schtick does not laughter prompt. If I failed to up with a punchline to a gag about children in cages, well, that’s because I’m a normal human being and if you, dear reader, came here looking for one, you, dear reader, are very sick. There was another explanation for my failure, however: one less flattering. Coming up with a working gag about something genuinely monstrous requires a capacity to invent an example of a very rarefied form of satire that only the rarest of talents can supply.

This, I do not have.

So hand over the gun, pardner, a demon from within says. And now go sit on the porch with the dog and that nice, cool pitcher of lemonade the nurse put out for you.

Fair enough. Trump can’t admit to his hugely poignant electoral loss, but I, the larger, and thus even more poignant soul, will admit defeat, as much as it shames me: and I even will do so right here, on my own porch.

In Weimar Germany, when setting up a joke about Nazis, cabaret comedians would sometimes announce that they were going to tell the joke in question very, very, very slowly so, in case any Nazis were actually present, they wouldn’t feel left out. This was necessary, the comic might add, because the party’s intellectual impoverishment was as obvious as a dead cow on the roof. Several of these, in fact. Berlin’s then prolific irony factory was quick and eager to draw one’s attention not only to the cows but to the flies and the stench, as well. The cabaret jab was funny because it was true, as Homer Simpson once astutely observed, and the tee itself is so good, it hardly mattered where where the ball itself ended up.

But for the joke to really work well, you have to put it–and keep it–in its pre-1933 context. It is kind of fun to Imagine a gathering of lummoxi germanicanus huddled around a corner table, with a picture of dear old mutti in their superego and a picture of half naked nibelungen in lederhosen crawling around in their ids, lifting their heavy brows and looking around the dark cabaret, suspecting that something is going on here, but they don’t know what it is.. In that funny yet bleak way. After 1933, though? Not so fun. And less so with every passing edict and invasion.

An already difficult and already complicated opportunity for laughter becomes that much more difficult and complicated and, ultimately, difficult and complicated jokes are not usually very funny, precisely because they are so difficult and complicated. One can admire the attempt to make fools of the fools, to give a raspberry to the moral runt in a brownshirt, and yet still cringe at the result. Even though Roberto Benigni drew upon the venerable motion picture work of masters such a Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and the Marx Brothers, his film Life Is Beautiful, for example, never quite convinced you that life was quite beautiful enough and would allow you to relax and have a smoke and a laugh. Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit, a more recent and more totalling car wreck of a movie, pursued a similarly ethical and comedic end. But in the end weird isn’t the same thing as funny. Sometimes, weird, in spite of what the academy says, is just weird.

And thus the deserved, and inevitable, retort arrives as scheduled.

But what about Mel Brooks and The Producers?

For just a little while, let’s keep the endlessly appealing figures of Bloom and Bialystock in the background–they look at us but don’t yet speak–and review some rules of road before we go any further. First: the scale of human destruction wrought by Donald Trump, however painful it may have been and might yet become, cannot be, and is not here being, compared to the scale of devastation wrought by Adolf Hitler. Second: there are innumerable examples and aspects of that human destruction, whether writ large or small, that just aren’t funny and never will be. Three: the presumed and genuine ethical injunction that such grotesques should be laughed at, should be mocked, should be ridiculed, is not a blank check, comically or artistically, as Begnini and Waititi have amply demonstrated.

Finally: while being Jewish unquestionably augments one’s moral permission, or imperative, to announce that the Führer had no clothes, there is nothing about being Jewish that assures that either the joker or the joke will necessarily be funny when being self-reflective. Permissible isn’t funny. Funny is harder than that. A circumcised comedian can still tell a Jewish joke that tanks and is unfit for public consumption, no matter how well the comedian tells it. There are unforgiving degrees of craft, artistry, discipline, and talent at play here, and it is that very professionalism that makes an oddity like The Producers–which is at once true and hellish and hilarious–work.

Thankfully, The Producers offers a shockproof master class on how to make even the hard stuff work. For example: although there is plenty of Hitler talk on the screen and stage, we’re always one step, or more, removed from the man. We are watching not a skewering of an individual, per se. There’s no deep dive into the guy’s fucked up–and, yes, ridiculous–psyche. Instead, we observe a deft treatise on Hitlerism, of sheepish mass psychology and, by extension, the phenomenon’s endless variants. It would take some expert editing, but you can imagine how, with the right creative team, P.W. Bothaism or Francisco Francoism or Josef Stalinism could just as easily make for a misguided schmuck’s wrong way ticket to infamy and self destruction. The details can vary and yet the zinger can stay as is. Groups of people are too easily mesmerized. Think about that on this day, America.

Similarly, note that Hitler as a character himself never shows up. Again, we are a remove, looking at a reflection and instead we meet a cracked actor by the name of Lorenzo St. DuBois–L.S.D., get it?–who likes to put on a socially inappropriate costume, somewhat in spite of himself. Hitler himself was not a funny guy. Lorenzo St. DuBois, on the other hand, is a hoot.

So everything in this framed, show biz world is thus approached at an angle, with distance, with irony in the true sense of the word. That is: Brooks says one thing but he means something else, altogether. Like Lorenzo St. DuBois, who has wandered out there into the Milky Way like Art Linkletter’s levitating daughter, there is a disconnect between the self and what the self says.

Bloom and Bialystock are not trying to wring the Naziploitation genre because they hate themselves: they’re doing it because they’re broke and have illusions of grandeur. The well heeled, sophisticated audience in Manhattan, which t thinks so highly of itself, fools itself into going with a gag that, by rights, should be grotesque. Everyone in this world does the opposite of what it looks like they’re doing, of what they’re trying to do, and what is shocking–and what gives The Producers it’s perfect bite–is that the truth of the matter gets lost, entirely, in all of the hypocrisy.

On the other hand, Hitler was, and Donald Trump is, incapable of hypocrisy. Lies swaddle both men in infinite layers, yes, but lying with intent is hardly the same thing being a hypocrite. With these guys, the purpose of one’s lies has remained true, unremitting, focused, fixed, and unwavering, throughout. They cannot be shamed because they have no capacity for the self-reflection that is necessary to shaming. Hitler signed a piece of paper in Münich, but did not violate the accord because he didn’t take it seriously in the first place and was probably sort of shocked that, given his past behavior, everyone could be so stupid as to think that a gentleman’s handshake meant anything to him. Similarly, does Donald Trump think that he really should still be President? Who knows. Who cares. Donald Trump thinks everything should be about Donald Trump and that is all ye need to know.

What you see is exactly what you get. Every. Time. Because they are incapable of change they cannot tell a lie. Or a joke.

Look at rare pictures of the two guys when they are caught laughing. Something, apparently, is considered funny. But something about the way the mouth has opened and the head is tilted back, gives the unfunny menace away.

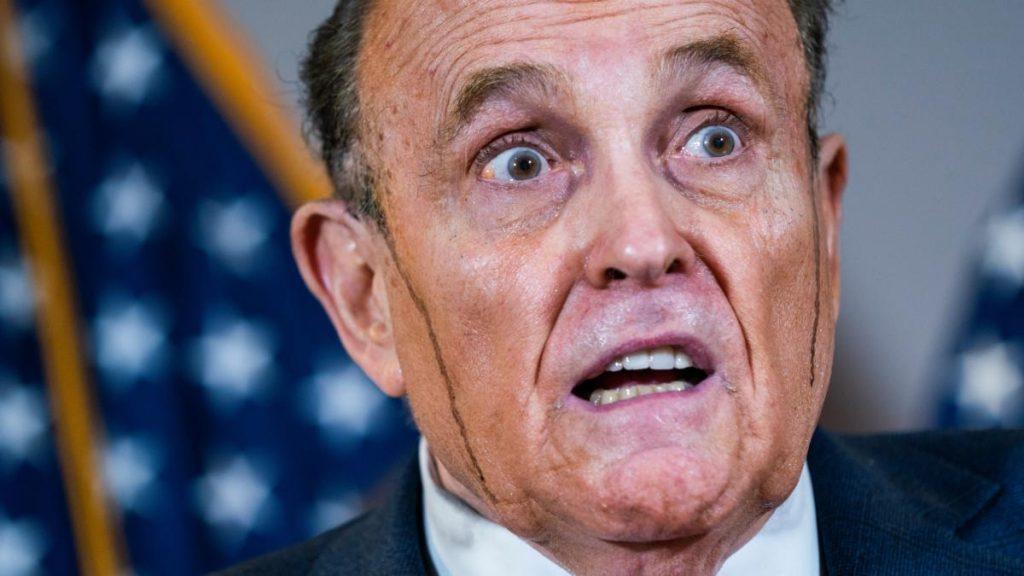

For decent examples of high irony in the Trump era—you have to turn to the characters just a bit removed from the bossman and his bedazzled, organized crime family. You have to turn to the figures at least somewhat farther out, those on the periphery, at least a few more steps away from the deadened center. Those who, presumably, could walk away from it, if need be. Lindsay Graham, in spite of his abundant hideousness, can make you chuckle now and then when you put together a split screen: on one side, his former critique of (fill in the obvious blank), and on this side, his current sycophancy about a certain butthole he smooches. Sydney Powell, when defending her riff on how Huge Chavez influenced the 2020 election, is quick to point out to Dominion Voting Systems that is what she said was not slander because no one would ever believe something so stupid. Rudolph Guiliani knew perfectly well that he wasn’t adjusting a microphone when he was caught with his hands unpleasantly in his pants in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. You knew it. Everyone knew it. And yet he went on and lied about it.

That’s funny.

What makes these peripherals appealing as quasi-characters is that they are capable of about-faced, swivel-heel change, of accomplishing the unintended, of suffering the occasional humiliation, of executing the class comic turn between anticipation and the brutual manifestation of the opposite and unexpected: e.g. the banana peel, pal, and the hidden camera, in Rudy’s case, which shows what he thought was hidden. And instead of the sex he thought he might have with Maria Bakalova, disguised as a conservative journalist, we see Giuliani humiliated. We see cel-drawn caricatures like Graham, Powell, and Guiliani backstage, so to speak, as they sit down in front of the make up mirror, preparing the face they use for the faces that they meet.

Just as most of us do. Every day. For all of our lives. For most of us, there’s always that spooky gap between that spot in your head, where you live, and the world, where you also live but which is rarely the same thing as that spot in your head. There’s always the shadow, falling between the motion and the act, as a famous anti-Semite once wrote. We may even feel a twinge of empathy for hapless, self-manipulating, or manipulated-by-others marionettes, like Lorenzo St. DuBois, because we know that we know the same, awkward gap between who we put out on the shelf for public display and who were are, in fact.

That imperfection, that space where the distance between the ideal and the real can be recognized and measured is the same space where accidents can happen and where something can turn out other than how we meant it. Sometimes that something, thank god, is funny. Further, it is generally agreed that an awareness of that space, that weird and vast wiggle room, so to speak, is one of the things that makes us uniquely human.

Human instead of being a mere object, for example, which typically has a single, unvarying purpose.

Trump fits this sociopathic and utilitarian suit perfectly, of course. He is on a single-minded mission to prove himself the greatest at everything, as we have, to our great misfortune, learned. In this way, out of all of the peripherals of the Trump era, Kayleigh McEnany came, or comes, the closest, in spite of her impeccably appropriate manners, to having the same fixity as her boss. Granted, God-the-Father-rather than God-the-Racist-Pappy-From-Queens-Who-Was-One-Vile-Real-Estate-Mogul sent her out on her mission, but she’s just as a fixed and terrier-like in that she will see whatever it is all that she is doing all the way to the bloody end when the field has at last been freed of all vermin, here and in heaven.

In another life, while practicing another profession, I had frequent occasion to sit, in private, in various carceral and psychiatric settings, with people who had committed heinous crimes. When I did this, no one else knew what the two of us were talking about. No microphone had been hidden under the table, if a table was even allowed. I rarely took notes. The code of my profession demanded strict confidentiality. In a sense, no zone could be more safe than that interview room, even though it was also always filled with varying degrees of dread. And yet, in all the days I spent in those confined spaces, no one ever confessed. No one copped to any previously withheld responsibility or culpability. The confession–which is only a factual acknowledgement of responsibility and says nothing about psychological or ethical implications–had either already taken place. Or it was never going to.

So it seemed. So it was likely. The story concerning the circumstances around and the justifications for the crime varied, a little, but the theme and the trajectory were always more or less the same,. The person would insist that, had I found myself in the same situation on that fateful day, I would have surely done just the same. It was incomprehensible that my reaction could have been anything otherwise, that there could be that sort of flexibility in my personality and in my response to the world. Instead, the person had typically been forced into doing it and now was misunderstood, persecuted, unjustly denied the right to speak, and sometimes even deserving of revenge, in fact, against all of those in street clothes, or uniforms, or in judges robes who had sinned against the victim in the orange suit.

Each, like Trump, like McEnany, remained–in this way–as stiff and predictable as objects.

The cinder blocks and metal doors and the sally ports with alarms ready to shriek and throw everything into lockdown at the slightest provocation were hardly all that kept the person trapped in order to, sometimes, serve either a real or metaphoric life sentence. The objectification of the self by the self, and the consequent fixity, was doing a perfectly fine job, already. The person was locked up, and in, and could not step out of their constructed personhood. A true persona was impossible to achieve. There never was a mask because there was nothing to hide or alter. Transgression of the self was out of the question as the self was built of stuff even thicker than the cement in the walls.

And in all of these many interviews and conversations, I don’t recall ever laughing. Not really. I may have feigned it, or done it for sort of real, perhaps to ease the tension, to make me seem trustworthy and accessible, to give myself some kind of moment of human space and blessed uncertainty, or I may have done so to go along with it what was going on, snorting enigmatically, for instance, about the joke being told to me about the difference a Jew and a pizza when in they find themselves in an oven because to do otherwise would only cause me more headaches and a lecture from me at that point was not going to change a damned thing and would, instead, just make it all that much harder to find out what I was there to find out.

But did I ever really laugh?

Not that I recall.

Thank god.