(A Peepstone Prequel)

Colin Powell at the United Nations, holding a vial of hypothetical anthraxon

February 5, 2002. Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images

Rene Magritte, 1927

In the shadows of the fallen towers, among the unsettled dust of souls, aside the grief and the post-traumatic stress disorder, it remains with us: a fundamental break in the bones of the body politic. The fracture took place in the time immediately after and hasn’t healed, and because we didn’t set it back on course, it stays with us, and has worsened, and taken on darker and stranger morphologies. As difficult as it is to name, we have to try, as it has namelessly become an essential habit, a pathology even, of our national unconscious.

The day seemed to change the scale of American political feeling. That’s what people talk about. What they remember. The day etched our national attachments in deeper grooves and sharpened our towering sense of both wrong-doing and right-making. In the noisy wake of that sharpness and those depths, it became difficult to hear and to see this other wreckage forming, one so subtle by comparison that it seems strange even to mention it. It’s even stranger to describe it as a form of violence.

The “war on terror” supplied the manifest cover for the cleave. Many terrible real-world things would find haven in that expanding bellicose shelter: the invasion of Iraq, which is our focus here, but also the war in Afghanistan, which has finally ended, messily; the practice of extraordinary rendition; the secret surveillance of U.S. citizens; the deploy of waterboarding and also the moralistic defense of it; undisclosed detention sites and enhanced interrogation techniques; pervasive racial profiling and its transformation into anti-immigrant nativism.

Not to mention the rampant, performative sadism of Guantanamo Bay.

The material effects of symbolic violence are not always easy to measure. Except when a case presents itself in such a florid way we cannot ignore it. Or can we? It is especially difficult to pay attention to symbols when terrible loss and impassioned vengeance flood our senses and define our national identity. Though it may be less visceral, the post-terror imaginary landscape of the U.S. has proved to be a deadly and enduring stylistic companion to the terrorist networks that would do us physical harm.

In all of the sober and solemn and mournful speeches by survivors and witnesses and former Presidents who commemorated the twenty-years-since-and-after, no one mentioned it. Not even former President George W. Bush, who was in fact the architect of this American stylistic fracture, at least the modern incarnation of it. In his widely cited speech, he called out the January 6 insurrectionists as “children of the same foul spirit” as al-Qaeda. Bush could have called out his own foul policy, born of homegrown grievance-turned-vengeance, for surely even he could recognize at least that much after twenty years. That much hindsight he couldn’t muster.

Our contemporary problems with truth-telling can be tracked back, in large part, to that day and what came after. Those problems have stayed with us, and they have deepened and become darker and more self-destructive. The genealogy is clear. They’ve given Bill Barr historical precedent and narrative alibi. They’ve led to the suicidally cultish anti-science movement as a full frontal attack on evidence and rationality. They have allowed purely invented election fraud to determine actual state law governing more restrictive voting practices.

Those who participated in the twenty year public commemoration of September 11, 2001, they all left out that part of the story: that in the aftermath of the coordinated attacks, and the loss of life, and America’s sudden membership to the club of the terrorized, in the long shadows cast by these events, we made a perverse pact with words and images.

Secretary of State Colin Powell delivered the terms of the contract. Inside the Bush administration, which had few spokespeople with bipartisan appeal, the one with greatest credibility had to make the case. That person was undeniably Powell. So he became the messenger. Nevertheless, prior to his speech, he had doubts. He questioned the evidence, as did key personnel inside the CIA. The doubts were not ambiguous, they were emphatic, in a thick-red-marker kind of way. Nothing had been verified. Many of the sources were questionable. Powell wanted more time to prepare the facts and make sure that he was on solid ground. But Bush and Condoleeza Rice had already booked Powell for a spot at the United Nations, before the Security Council, on February 5, 2002.

And so off to the UN went Colin Powell, to tell a story no one wanted to disbelieve, quieting the red-pen alarms going off in his mind.

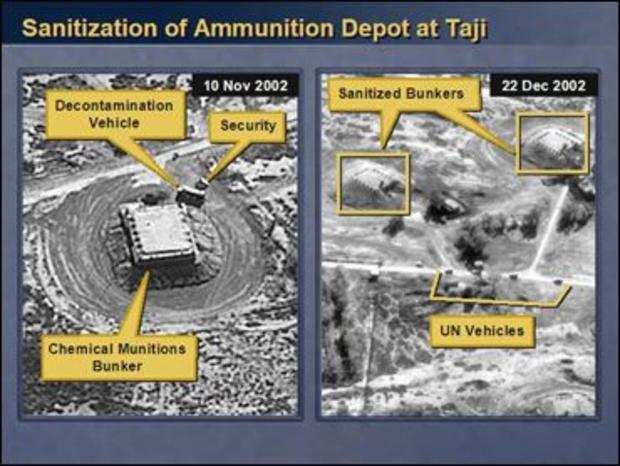

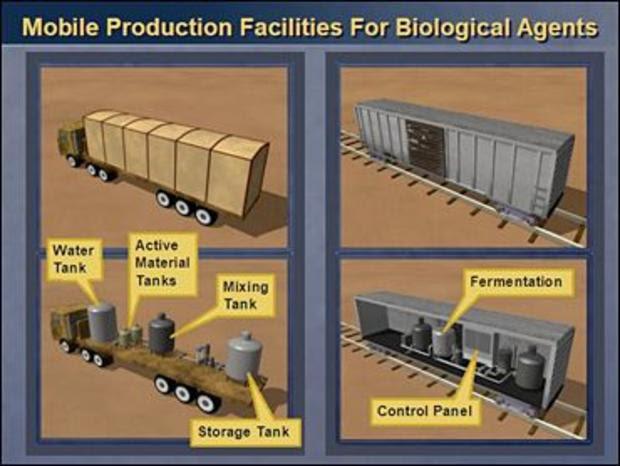

In the austere halls of the United Nations, he rendered what was taken, by nearly everyone, to be unimpeachable evidence of Weapons of Mass Destruction, under a secret and illegal system of production by the regime of Saddam Hussein. His presentation was anchored by a great number of satellite and surveillance images, each authorized with the State Department imprimatur, all of them dark and blurry and indefinite, all meant to illustrate a vast capacity for weapons production. Each image contained arrows and thought balloons, designating what Powell purported each image to mean.

I cannot tell you everything that we know. But what I can share with you, when combined with what all of us have learned over the years, is deeply troubling. What you will see is an accumulation of facts and disturbing patterns of behavior.

Powerfully persuasive at the time, his delivery was intense and unflinching, and if his evidence was not reliable, his narrative voice did not betray a bit of ambivalence.

My colleagues, every statement I make today is backed up by sources, solid sources. These are not assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence. I will cite some examples, and these are from human sources.

It was fictitious entirely. Full of fabrication. No one ever found any Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq. At the United Nations that day, Powell’s lies numbered in the dozens, maybe more.

Let me say a word about satellite images before I show a couple. The photos that I am about to show you are sometimes hard for the average person to interpret, hard for me. The painstaking work of photo analysis takes experts with years and years of experience, poring for hours and hours over light tables. But as I show you these images, I will try to capture and explain what they mean, what they indicate to our imagery specialists.

Powell’s hellish pact with words and images led us to two endless, needless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Trillions of dollars. Thousands of lives lost. Thousands more mired in permanent trauma and disability. The term “collateral damage,” though coined after the second world war, came into wider fluency as a way to describe the deaths of Afghans and Iraqis killed in drone strikes run amok. The “antiterrorist” wars wrought by Powell’s deceit, ironically, fomented greater terrorism against the U.S., a nightmarish cycle of vengeance and retribution.

René Magritte titled his pipe series the “treachery of images,” a visual meditation on representation and its ironies, absurdities, and deceits. He puzzled deeply enough about the conundrum of words and images to remake the piece in different media after several decades and to retitle it, the tune and also the words. His initial fascination coincided with the advent of synchronous sound in cinema, when onscreen moving lips were gratified with a simultaneous soundtrack, creating the appearance of wholeness, a seeming seamless fusion of sound and sight.

Magritte’s remake of the pipe, for all its homey faux-wooden framing, adds the sign of smoke, the sure index of fire, which could ignite the entire complex message. A post-war pipe this is, one that has outlasted unspeakable nihilism, but just barely and only for now.

Rene Magritte, 1964

At the time, Powell’s presentation had its critics and counternarrators, who questioned the veracity and integrity of what he presented. Powell also had narrators who fed him and his story spinners at the State Department the plotlines they wanted to hear. One Powell source sported the codename “Curveball,” for his notoriously unreliable intel. Said one CIA operative managing the evidence underlying Powell’s report: “Curveball was a slug. Curveball was a slime. But Curveball didn’t make anybody believe something that they didn’t want to believe.”

Criticism of Powell’s presentation came mostly from abroad and from within Iraq, which in retrospect shouldn’t be a surprise. To question our antifactual and moralistic march to war against an imagined enemy and its fictitious armaments was at the time and probably still is perceived to be an assault against America itself. Nevertheless, at least one counternarrator described Powell’s image-text spectacle this way: “This was a typical American show, complete with stunts and special effects,” said Iraqi Lieutenant Amir Al-Asaadi; “cartoons,” he called Powell’s collages, and evidently, some quite literally were.